Chapter 6

Great opportunities for recreational activities and learning experiences

The South Downs offers a wide range of recreational and learning opportunities to the large and diverse populations living both within and on the doorstep of the National Park, and to visitors from further afield.

With more than 3,300 kilometres (2,050 miles) of public rights of way and the entire South Downs Way National Trail within the National Park there is exceptional scope for walking, cycling and horse riding. Many other outdoor activities take place such as paragliding, orienteering and canoeing. There is a chance for everyone to walk, play, picnic and enjoy the countryside, including at Queen Elizabeth Country Park in Hampshire and Seven Sisters Country Park in East Sussex.

The variety of landscapes, wildlife and culture provides rich opportunities for learning about the South Downs as a special place for the many school and college students and lifelong learners. Museums, churches, historic houses, outdoor education centres and wildlife reserves are places that provide both enjoyment and learning. There is a strong volunteering tradition providing chances for outdoor conservation work, acquiring rural skills, leading guided walks and carrying out survey work relating to wildlife species and rights of way.1

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating how access to nature and opportunities for outdoor activity can have an important impact on physical and mental health and well-being.2 Benefits range from opportunities to increase physical activity through walking and taking part in sports, to the mental health benefits of green exercise (exercise taken outdoors in a natural or semi-natural environment), or simply being close to nature. In addition to health benefits for individuals, access to green spaces has wider social benefits: providing opportunities for social interaction and helping to create a sense of community.3

This chapter looks at opportunities for access, recreation and learning experiences, focusing on users and participation, and considering any barriers that prevent some people from experiencing and enjoying the National Park.

Access on land

Rights of way

The South Downs National Park has the longest rights of way network of all national parks in the UK, with more than 3,300km of footpaths, bridleways and byways. This network, including the 160km South Downs Way National Trail, is without a doubt the National Park’s most significant recreational resource. It is the primary means by which people access and enjoy the National Park, providing opportunities for many recreational pursuits from gentle strolls to exhilarating rides. The key facts box details the footpaths, bridleways and byways that make up the rights of way network.

|

|

Key facts: Rights of way |

|

Footpaths 1813km |

|

|

Bridleways 1213km |

|

|

Byways open to all traffic (BOATs) 77km |

|

|

Restricted byways 229km |

|

|

(Included in above figs. is the South Downs Way National Trail 160km) |

|

|

|

|

|

The South Downs Way © Stewart Garside |

|

Managing and maintaining rights of way

The four local highways authorities (LHAs)4 are responsible for the management and maintenance of the public rights of way within the National Park. As people’s ability to enjoy the area relies heavily on the quality and accessibility of the paths and trails, reliable and consistent data about the condition of the rights of way network across the National Park is vital. A recently agreed Joint Accord5 between the National Park Authority and the LHAs sets out how we will work together to ensure that rights of way and access opportunities are of a consistently high quality and that information on the condition of rights of way is regularly updated and made available.

|

Box 6.1 Rights of Way Improvement Plans Rights of Way Improvement Plans produced by local highways authorities are aspirational plans identifying potential improvements to the rights of way and access network. We will work with the LHAs and the South Downs Local Access Forum to identify those improvements that will bring the most benefits to users. |

|

Box 6.2 South Downs Way National Trail The South Downs Way National Trail is the most significant element in the rights of way network in the National Park. At 160km (100 miles), it is one of only 15 National Trails in England and Wales and, as a bridleway, is the only National Trail in Britain which is fully open to walkers, cyclists and horse riders for its entire length. The South Downs Way is also the only national trail entirely within a national park. Two main groups use the trail: those walking or riding the entire length of the Trail and those using just part of the Trail for a shorter visit, usually combined with use of the wider rights of way network. Using data from people counters buried under the Trail and other visitor surveys, we estimate that around 20,000 people complete the whole length of the South Downs Way each year, while approximately 20 million visits are made to shorter parts of the Trail. Later in this chapter we discuss the impacts of the volume of people using the Trail and the different types of use. National Trail Quality Standards exist to provide a framework for the management and maintenance of National Trails and to enhance people’s enjoyment and experience. The Key Data box at the end of this chapter highlights 2 of the 24 standards against which the state of the South Downs Way can be measured. |

For more information about Rights of Way and the Joint Accord |

Other long distance trails and promoted routes

Access to the National Park is enhanced by a number of long distance trails, cycle routes, quiet lanes6 and other promoted routes.7 Examples of promoted routes include the:

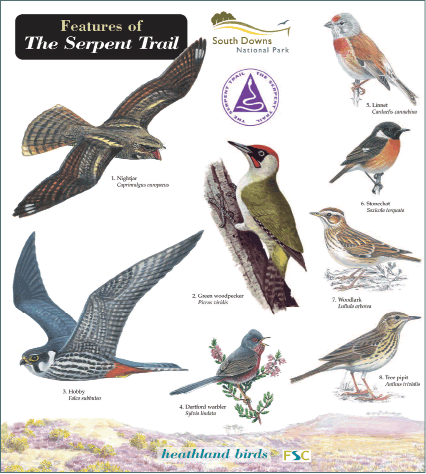

Serpent Trail: a 107km footpath that snakes its way through the countryside from Haslemere to Petersfield, showcasing some of the outstanding landscapes of the greensand ridges and linking areas of Access Land; and

Shipwrights Way: a 96km route which runs from Alice Holt Forest to Portsmouth. On completion, the route will be available for walkers, cyclists and, in parts, horse riders, and buggies and trampers for the disabled.

Open access

Access Land is land which is open to the public under the Countryside and Rights of Way Act (CRoW) 2000. The public are able to walk freely over this land without having to stay on paths. In the National Park the majority of the Access Land is unimproved downland with some areas of heathland in the Western Weald and a number of Common Land sites. Access Land is classified as mountain, moor, heath, down and registered Common Land, so the amount of CRoW Access Land mapped in the National Park reflects this.

We are the access authority for Access Land and it is our job to ensure Access Land is open to the public. While the majority of the designated sites are available for public use, some 16 sites could be described as unavailable or inaccessible.8 This can be for a number of reasons. For example, some are ‘island’ locations, so called because there are currently no rights of way or permissive routes by which the public could reach them. In other places, dense, impenetrable scrub means that some sites are unavailable to walkers. We are working closely with landowners to enable public access to all the designated open Access Land.

The Serpent Trail is an example of one route which successfully joins up areas of Access Land (CRoW Access Land, Common Land and other open access) providing an exceptional recreational experience.

|

|

Key facts: Access Land |

|

4.4 per cent of the National Park in 311 separate sites has been designated as Access Land (8,500ha). |

|

|

An additional 5 per cent of the National Park is other open Access Land such as Country Parks and land managed by the National Trust or Forestry Commission. |

|

|

|

|

|

Enjoying open Access Land at Butser Hill © SDNPA |

|

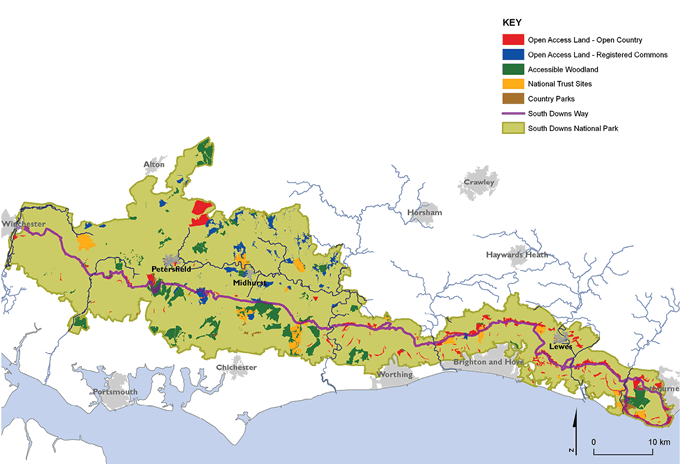

Map 6.1

The main types of open Access Land in the National Park.

Maps prepared by: GeoSpec, University of Brighton; February 2012.

Sources: Natural England, 2003; Woods for People, 2010; National Trust, 2011; Natural England, 2010

Ordnance Survey Crown Copyright © Licence No. 100050083

Access to water

The National Park has a diverse range of rivers, coastal and inland waters, which provide a rich resource for wildlife, biodiversity and, in some areas, recreation.

A public right of navigation exists on the tidal reaches of the rivers and boating activities from canoeing to motorboat cruising take place. However, the value of the tidal rivers for water activities is constrained by the limited number of access points. It is therefore often only the most determined who take to the river and experience the delights of the National Park by water.

The cut off meanders of the river Cuckmere provide an excellent resource for canoeists and a safe learning environment for beginners taught at the Seven Sisters Canoe Centre © www.cvcc.org.uk

See the story of water in the National Park in the Water Fact File.

Activities for everyone

On land

Walking is probably the most popular of all activities taking place in the National Park. In the 2003 South Downs Survey, 25 per cent of visitors cited walking as the primary reason for their visit, with a further 37 per cent indicating walking as a secondary reason.9 The rights of way network is also used for off-road running and orienteering.

Cycling and mountain biking are increasingly popular activities. Data from the South Downs Way online surveys and people counters between May 2009 and April 2012 indicates that at least 30 per cent of users are cyclists with some locations identifying more than 60 per cent of users as cyclists.10

With more than 1,500km of bridleways, restricted byways, and byways open to all traffic (BOATs), horse riding is a significant activity in the National Park. Carriage driving takes place on restricted byways and BOATs and also, by permissive agreement, on some National Trust Land. Accessing bridleways can be an issue for riders, with a shortage of parking for horse boxes across the National Park: some key operated schemes are in place but height restriction barriers prevent access in many public car parks.11

We need help with mapping the bridleway network in relation to the availability of horsebox parking and equestrian facilities. |

Motorcycle and 4x4 use of BOATs is determined by their location, with the majority of BOATs located in Hampshire. Rural roads are also used by recreational motorcyclists and by classic car owners and regular classic car rallies take place in various locations across the National Park.

In recent years a number of new sports and activities have sprung up, including mountain boarding and zorbing. These activities are generally provided by commercial operators and people pay to take part. Alice Holt Forest and Queen Elizabeth Country Park are also home to commercial recreational ventures such as cycle hire, Laser Games and the tree-top adventure GoApe. In fact, many recreational activities in the National Park are organised by independent operators.

We need data on number, type, scale and distribution of these businesses. |

There has been a marked growth in the number of mass participation events such as walks and cycle rides. Records for the period 2010–2012 show approximately 40 registered events take place annually on the South Downs Way during the period March to October. However, events are known to take place all year round and many smaller organised events may not be registered.12 While such events are generally seen as a positive thing, there is concern that they may also contribute to path erosion, litter, traffic congestion and car parking problems.

Generally, recreational activity is unevenly distributed across the National Park. The 2003/04 visitor survey indicated that 91 per cent of recreational visits took place in Sussex, with a significant percentage of these visits concentrated at popular sites such as Devil’s Dyke and Seven Sisters Country Park.13 A number of factors influence the distribution of visitors, including ease of access – the availability of public transport, car parking and other associated facilities. Awareness of alternative sites is also a factor influencing destination choice and in order to manage pressure on vulnerable sites a review of the reasons behind visitors’ choice of destination would enable us to promote and develop alternative areas.

Mass participation events like the British Heart Foundation Challenge are excellent opportunities for healthy exercise © British Heart Foundation

On water

Non-tidal rivers are generally not available for boating unless by prior agreement with landowners. Angling opportunities in rivers, lakes, ponds and the sea abound. Data from the Environment Agency indicates that angling and recreational sea fishing takes place at more than 160 different locations across the National Park.14 Coarse angling tends to take place either within a traditional club structure where clubs and societies lease riparian fishing rights or at commercial coarse fisheries, where day tickets are available, usually on still waters or ponds. The chalk rivers at the western end of the National Park are high value game fisheries of national and international significance, whereas the coarse angling, sea fishing and other water related activities such as canoeing and boating have a more local or regional audience.

While we currently have little data on participation in and demand for water based activities in the National Park, the 2011/12 visitor survey will show the percentage of visitors and residents participating in water-based recreation.15

In the air

There are a number of significant sites for air sports, with hillside take off points for paragliding and hang gliding in various locations across the National Park. Mount Caburn, just outside Lewes, is popular with a number of paragliding companies and Salt Hill, East Meon, is also used for paragliding and hang gliding. Model aircraft flying, hot air ballooning, gliding, microlight and small aircraft flying also take place. There is concern that noise from some flying activity may impact on tranquillity. However, we know relatively little about the provision of and participation in air sports and would like to build up a more accurate picture of these recreational activities.

We need data on the provision of, and participation in, air sports. |

Paragliding at Devil’s Dyke © David Russell

|

Case Study Karen Whittaker

Karen Whittaker works for the National Trust as the Visitor Experience Project Manager for the South Downs, based at Saddlescombe Farm on the route of the South Downs Way, near Brighton. The National Trust has recently opened a campsite at the farm and is planning a camping barn to encourage people to enjoy the route in a more sustainable way. “The South Downs Way is well loved and people come from far and wide to walk its length, do ‘boot sized’ chunks over a weekend, or just pop up on the bus after work and enjoy what John Constable described as ‘the grandest view in the world’. Good news travels far and I have recently taken a booking from someone in New Zealand planning to walk the South Downs Way. A school group recently visited from inner-city London and the children loved it, this area is a real breath of fresh air for many people. Even somewhere that looks wild and unspoilt takes careful land management. The National Trust manages over 6,000ha of land on the South Downs cared for by more than 35 wardens working with a huge team of volunteers. Without them the area would look very different. All year round you will spot teams working on the steep slopes clearing scrub or even recently making over the chalk horse on the side of the hill near Birling Gap. The South Downs wrap themselves around many villages, towns and cities which benefit from being on their doorstep – economically, environmentally and in quality of life. The people who walk and cycle here utilise the local shops, accommodation, transport and outdoors sports businesses, benefiting local communities and visitors alike.” |

Issues with recreation

Recreational users can cause problems for land managers, for example, by allowing dogs to disturb grazing animals. Illegal use of rights of way by motorised vehicles can be a problem in some parts of the National Park, although this does not appear to be widespread. Conflicts of interest occur in some places, for example, where 4x4 vehicles have caused significant damage to some BOATs making them inaccessible to other users. As part of our 2011/12 Visitor Survey, we spoke to land managers to gauge the scale and nature of the recreational impacts they experience. The results will inform the basis of our work to promote responsible use of the countryside.16

Health and well-being

It is generally accepted that access to open space and the natural environment can provide health benefits, particularly in relation to heart disease, stroke and mental health. The New Horizons Department of Mental Health strategy states that the ‘Increasing availability of urban green spaces, views of and access to safe green spaces and greater engagement with the Natural Environment has been found to have multiple benefits for mental and physical health.’17 The Government is therefore looking to National Parks to help deliver its targets to improve the health of the nation.18

Having access to the natural environment is crucial if communities inside and within easy reach of the National Park are to benefit from the health and well-being opportunities provided. The New Horizons study indicates that generally people are healthy in the National Park; where health issues do exist they tend to be in the urban areas surrounding the National Park.

For a map showing indices of multiple deprivation for health. |

A recent study commissioned by Natural England, on behalf of the South Downs National Park Authority, examined the existing access network using the Accessible Natural Greenspace standards (ANGst) as a guide and identifies where the network is deficient in the National Park and surrounding local authority areas.19

|

Box 6.3 Accessible Natural Greenspace (ANG) ANG is defined as sites which are fully accessible to the public in the sense that people are free to roam at will. This definition includes country parks, community woodlands, some nature resources and publicly accessible greenspaces within urban areas which have a natural character. |

While the statistics suggest access to ANG is relatively good across the National Park, there are some locations, particularly in urban areas, where the population has limited access. This data, when overlaid with information on the density of the public rights of way network highlights areas immediately adjacent to the National Park where communities lack access to both rights of way and ANG.

A more detailed analysis was carried out in one district council area (Chichester), including an examination of health scores in relation to ANG. Some areas outside the National Park which lacked ANG had the lowest health scores for the district. Similar detailed analysis of the data for the National Park would help determine priority areas for the creation of more Accessible Natural Greenspace to serve the needs of the communities within and adjacent to it.

For more information on Accessible Natural Greenspace in the National Park. |

Barriers to access

While we know many people every year are able to visit, enjoy and learn about the National Park, there are also large sections of the population who never visit the National Park or experience outdoor recreation. Learning in the Natural Environment (LINE) has been shown to provide direct education, health and psychological benefits and indirect benefits ranging from social to financial.20 Yet, many people and young people, in particular, are losing their connection with nature which some term ‘Nature Deficit Disorder’.21 According to Kings College, London, ‘This ‘extinction of experience’ has a detrimental long-term impact on environmental attitudes and behaviours.’

For more information on Nature Deficit Disorder. |

The proximity of the National Park to major urban centres whose population is both diverse and, at times, disconnected with the opportunities for recreation activities and learning experiences that the National Park provides, presents both opportunities and challenges.

In this section, we consider what we know about who visits the National Park and explore the possible reasons why some people do not visit.

Physical and economic barriers

In some cases people do not visit because of physical or economic barriers. For instance, in the 2003/04 Visitor Survey, 17 per cent of non-visiting households in the catchment cited not having access to a car as the main reason for not currently visiting the National Park.22

Public transport, where it is available, is not generally associated with recreational travel and, unless actively promoted through initiatives such as Discover Bus Walks, or especially targeted towards leisure users such as The Breeze Up to the Downs Bus, it tends not to be the usual means by which people visit the National Park. In addition the cost of transport to the National Park has been identified as a barrier to access for some groups, including schools.

Physical barriers may prevent people with disabilities from enjoying the National Park. Gates, stiles, uneven path surfaces or steep gradients can all be barriers. As much of the area is farmed, there are many thousands of gates and stiles on rights of way and Access Land for the purpose of stock control.

|

Box 6.4 Disability access At a meeting of the South Downs Local Access Forum in January 2012, members heard of the access difficulties experienced by Hampshire Roamability and 4 Sight Ramblers. Barriers included stiles on footpaths, unsuitable surfaces, uncertainty about the presence of livestock and a lack of information about suitable paths and trails.

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Disabled user on accessible path at Beachy Head © Anne Purkiss |

Cultural and social barriers

Cultural barriers can range from generational poverty to fears and misconceptions, and lack of appreciation and understanding of the physical, emotional and social benefits of spending time in the outdoors. A lack of appropriate information on opportunities for getting involved can also act as a significant barrier.

Under-represented groups

According to the National Park Circular, 2010, some groups, such as ethnic minorities, young people, disadvantaged groups and disabled people, visit national parks less often than others. A proactive approach is therefore required to overcome the barriers preventing these groups from visiting and experiencing national parks.23

In fact, the South Downs Visitor Survey, 2003/04, showed those who visit are more likely to be older, car-owning white adults in employment, and from higher occupational grades. Those least likely to visit are young adults, ethnic minorities, people in low-income jobs and those who do not own a car. Only 3 per cent of all visitor groups included one or more people with a physical or mental health disability.

In terms of socioeconomic group, only 22 per cent of visitors fell into the C2DE social grading, again under-representative of the regional demographic where 49.9 per cent are within this socioeconomic demographic. The demographics of the National Park are explored more fully in Chapter 8.

Other groups that are statistically under-represented in the visitor profile include people from black and minority ethnic (BME) groups. Within the 2003/04 visitor survey BME visitors made up less than 1 per cent of the visitor profile. Nationally, 10 per cent of the population are from BME backgrounds and within the south east region this figure is considerably higher. Mosaic is a three-year project led by the Campaign for National Parks in partnership with all the English national parks and the Youth Hostel Association (YHA) funded through Access to Nature as part of The Big Lottery Fund’s Changing Spaces programme. In the South Downs National Park, Mosaic has resulted in the recruitment, training and support of 29 volunteer Community Champions who work with us (and 6 joint Community Champions with the New Forest National Park) and its partners to address the barriers preventing BME groups from visiting and enjoying the National Park.

|

Box 6.5 Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment (MENE) In 2009, Natural England, the Forestry Commission and Defra commissioned a new survey called Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment (MENE) to provide baseline and trend data on how people use the natural environment in England. We have commissioned bespoke analysis of this survey data for the National Park which will enable us to develop our understanding of how people engage with the natural environment. This will underpin our work to remove barriers and open up opportunities for all sectors of society.24

|

Learning within the National Park

Informal learning

The National Park provides a wealth of informal learning experiences where people can develop a real ‘sense of place’ and become stewards for its future. These informal learning opportunities include public events, orga nised activities such as the Duke of Edinburgh Award and uniformed group visits, visitor attractions including the wealth of cultural and heritage sites, outdoor learning establishments and a host of publications and new media.

Public events are an important way of connecting with the huge potential audience around the National Park. In 2010/2011 we took part in 26 events and the highly visible, popular and visual displays were seen by more than 200,000 people. We engaged directly with around 15,000 people at these events. The staffing for these events included 80 days of volunteer time.25

In addition to these public events, many organisations and societies provide guided walks on a variety of themes. For example, the South Downs Society offers a wide spectrum of walks and talks catering for all levels of ability. Their Green Travel Walks week from 17–24 September 2011 provided 15 walks in a variety of locations around the National Park including East Meon and Ditchling Beacon, attracting a total of 127 participants. Other organisations providing broad programmes of walks and talks include the Sussex Wildlife Trust, the Ramblers, the National Trust and site specific providers including the Gilbert White Museum in Selborne.

The SDNPA attends almost 30 events across the area each year © SDNPA

Community participation in conservation activities is another important aspect of informal learning. For example, the Steyning Downland Scheme links people with different interests or knowledge promoting learning and building a positive experience of community.

For more information about the Steyning Downland Scheme. |

Figures on groups such as Brownies, Scouts and Girl Guides, and Duke of Edinburgh Award participation are less well known at present. There is work to be done to gather baseline data for this important area of participation which will begin in 2012/2013.

Formal education

Those in formal education are a key audience for the National Park with several hundred thousand school and college learners resident within and around it and rich opportunities to promote lifelong learning.

There are 738 schools inside or within 5 kilometres of the National Park boundary (86 of which are inside it).26 These represent formal education settings from Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) through to sixth form colleges, and include both independent and private sector provision, along with special schools. These schools cut across the three county council areas and unitary authority of Brighton and Hove and provide a huge potential audience for learning experiences within the National Park. The available information on special school provision and Early Years Foundation Stage is less accurate and there are providers other than schools within this sector that may not appear on the current database.

For a map of schools within the National Park. |

We need help with data on Early Years Foundation Stage and Special School provision as this is currently less well represented on the database. |

The Visitor Survey 2003/04 educational use questionnaire conducted by Tourism South East (TSE) provided evidence of school engagement with outdoor providers within the area of the now South Downs National Park. This survey was completed by 238 schools in and around the National Park and indicated that the vast majority of schools (97 per cent) were aware of the area. Of those surveyed 69 per cent had visited or were planning to visit the area for educational purposes during 2003/04.

This data, although very useful in building a picture of school engagement with outdoor learning provision, is now outdated, particularly as the results were gathered before the South Downs was granted National Park status. A new survey was commissioned as part of the 2011/12 visitor survey of the National Park which includes similar questions to the 2003/04 data. Early results from this survey indicate that while only 60 per cent of responding schools have visited or plan to visit the National Park this academic year, 88 per cent are interested in further developing learning outside the classroom opportunities.27 This data will be enhanced by a comprehensive survey of all schools within the 5km buffer as part of the innovative Our South Downs partnership learning project launched across the National Park in 2012 by the South Downs National Park Authority and the national charity, Learning through Landscapes.

There are around 37 key providers of outdoor learning opportunities across the National Park with many other smaller scale providers working across a range of thematic areas including environmental education, wildlife sites, country parks, museums and heritage sites, farm visits and outdoor adventurous activities. These providers present a rich and varied offer to both formal and informal education sectors. Currently eight of these providers have gained Learning Outside the Classroom Quality Badge status, demonstrating the provision of high quality learning experiences. This figure is likely to rise as the badge becomes more widely known within formal education audiences.

Children getting their first taste of outdoor learning at Alice Holt © Forestry Commission

In June 2007, 29 environmental centres were surveyed across both East and West Sussex as part of the Wildfowl and Wetland Trust (WWT) Consulting Review of Environmental Centres in the Pan Sussex Area. The results of this survey reveal the total number of educational visits per year for the 21 centres that were able to supply data was 80,118 – a huge formal education audience.

In addition to this outdoor learning provision there are currently 16 higher and further education establishments on the South Downs Learning Partnership providing a wide range of courses and qualifications from foundation learning, vocational Certificates and Diplomas, GCSEs, A Levels, Foundation Degrees to Degrees across all subjects. First brought together in September 2011, the Learning Partnership aims to provide an effective mechanism for communication between academic institutions in and around the National Park and the South Downs National Park Authority. There are numerous informal links between the schools, colleges and universities within and around the National Park. However, these are not well documented and more information is required to achieve the vision for learning within the National Park. The development of a South Downs National Park Research Strategy will be key to addressing this gap.28

Despite this high level of learning provision across the National Park there are still areas that experience deprivation in terms of education, skills and training. Two of these areas are among the 20 per cent most deprived nationally, 27 are among the 20 per cent least deprived nationally.

For a map showing indices of multiple deprivation for education, skills and training. |

Interpretation and information

Interpretation, or helping people to make sense of the landscape, wildlife and cultural heritage, is a key mechanism for communicating with the diverse audiences in and around the National Park. It increases understanding of this special place and enhances visitors’ experience. Interpretation is available across the National Park, much of it provided independently by a range of partners and stakeholders.

To gather baseline data a quantitative and qualitative audit of interpretation across the National Park was undertaken between October and December 2011.29 In total, 35 key sites representative of the National Park were included. Some of these are complex locations with several stories to tell and multiple items of interpretation. The sites correlate with those selected for the South Downs National Park Visitor Survey (commissioned September 2011). The interpretation audit will support and enhance the findings of the visitor survey. Key partners providing interpretation across the National Park were also interviewed as part of the research including the National Trust, Forestry Commission, Hampshire Wildlife Trust, Sussex Wildlife Trust and Natural England.

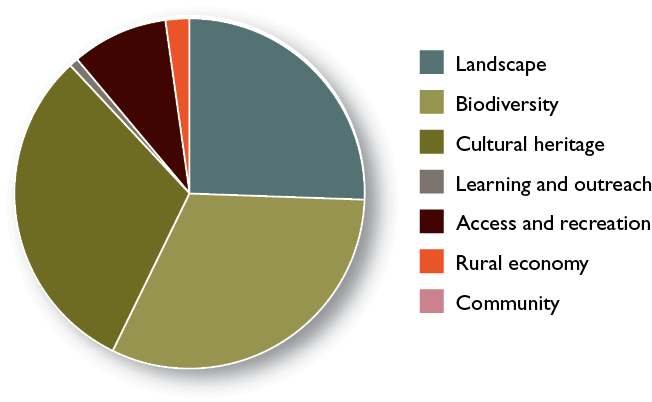

The audit concluded that the main topics currently interpreted are:

1. biodiversity;

2. cultural heritage;

3. landscape; and

4. recreation.

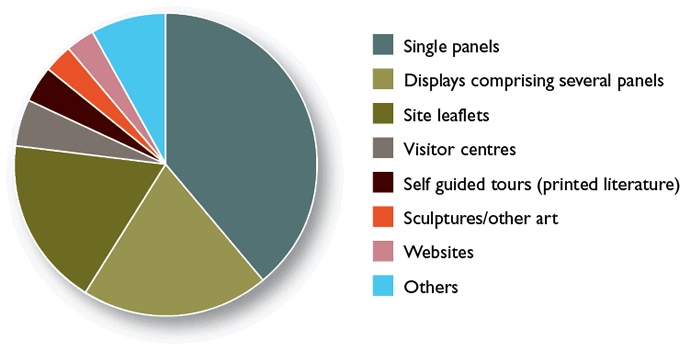

Figure 6.1 Interpretative theme

Source: South Downs National Park Interpretation Audit (December 2011) SDNPA

Other topics were less well represented through interpretive means, especially geology and land management, and in some cases there were mixed messages, particularly surrounding heathland interpretation.

Interpretation across the National Park takes many forms, although much is in the form of traditional means of display panels and leaflets. Of the 87 interpretive items assessed during the audit, 29 per cent were panels, 20 per cent displays and 18 per cent leaflets. Other media included websites, visitor centres, museums, sculpture or other art presentations, and self guided tours using printed literature.

For more findings from the Interpretation Audit. |

Figure 6.2 Interpretation method

Source: South Downs National Park Interpretation Audit (December 2011) South Downs National Park Authority

Information is provided across the National Park in various forms, including extensive printed literature such as walks leaflets, public transport guides and special-interest publications.30 There is also a growing, but still fledgling, use of new media to provide both information and interpretation about the National Park. This includes the use of mobile phone Apps such as the Sussex Wildlife Trust App and one currently being developed by the South Downs National Park Authority.

The 2003/04 Visitor Survey investigated the use of information sources by visitors. Maps or other sources of information had been used before or during the visit by 30 per cent of all visitors, including 25 per cent of all day visitors and 59 per cent of overnight visitors. Ordnance Survey maps were most frequently mentioned by these visitors (27 per cent), particularly by staying visitors. In contrast, day visitors were most likely to state ‘previous knowledge of the area’ as their main source of information (34 per cent).31

Volunteering

Volunteering is fundamental to the life of the National Park, enabling vital conservation and access work to be carried out along with rural skills development, guided walks and survey work relating to species and rights of way. This significantly enhances the capacity of organisations to deliver National Park purposes. The commitment and involvement of local people helps communities to develop a closer relationship with their countryside and fosters better understanding of the issues relating to its management. In essence, volunteers become ‘ambassadors’ for the National Park. Volunteering opportunities, particularly outdoors, also offer recognised mental and physical health and well-being benefits to those taking part.

In recognition of its importance, an audit of volunteering opportunities across the National Park was conducted in January 2012. This identified 165 organisations offering volunteering opportunities which were pertinent to the National Park’s purposes.32 This amounts to an estimated 10,500 people volunteering in the National Park on an annual basis, collectively undertaking around 91,000 days of voluntary work. If the national minimum wage of £6.08 per hour is applied to this, the work can be valued as contributing around £3,872,900 to the environment and culture of the National Park.33

The importance of volunteering within ‘active communities’ is explored in Chapter 8.

|

Case Study Marilyn Marchant

Marilyn Marchant has been a volunteer ranger in the South Downs for four years. She works one day a week in the eastern end of the National Park. “I first got involved in volunteering as I wanted to have more time for myself and to get out on the beautiful South Downs. As well as the opportunity to learn new skills and meet new people, the physical work really appealed to me. To spend time every week in the great outdoors has been life changing. Volunteering gives me such a buzz. Discovering new places off the beaten track, working with new friends and feeling like I have really made a difference. I have learnt so much about the local landscape and appreciate the diversity and accessibility of it even more. Each week is different, depending on the time of year we could be carrying out scrub clearance, coppicing or processing trees that have come down or need to be cleared. The work can be very demanding – who needs to go to a gym? The work not only assists in the effective land management of the National Park but also has a beneficial effect on biodiversity. There is a great social element to volunteering and I have met a wide range of like-minded people from different backgrounds, all of whom bring their own unique skills and expertise, as well as fun, to the team. There are 5–9 volunteers who go out on the same day as me. We all regularly work together and have become great friends.” |

The South Downs Volunteer Ranger Service (VRS) is a key part of this volunteering effort. Celebrating its 30th anniversary in 2011, the 311 volunteers in the VRS voted overwhelmingly on 1 April 2011 to affiliate to the South Downs National Park Authority.

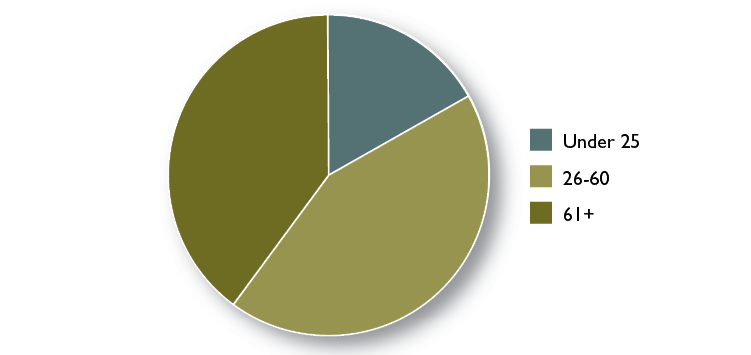

Figure 6.3 National Park-wide volunteer age profiles

Source: South Downs National Park Authority (2012) South Downs Volunteer Audit: Resources for Change, SDNPA

Trends over time show that the total number of volunteers within the VRS has increased steadily over the last decade but with a slight decline evident in the last 12 months. This can be attributed to the loss of key volunteer positions and a freeze in volunteer recruitment during the establishment of the National Park. The VRS carried out 729 tasks in 2010/2011, equating to 5,686 days of volunteering effort.34

This breadth and level of volunteering makes an immense difference to the National Park and furthers the opportunities for recreational activities and learning experiences for many thousands of volunteers.

For more data on volunteering. |

|

Key data: Great opportunities for recreational activities and learning experiences South Downs Way National Trail The National Park Authority, working with our partners, will monitor progress against two standards from the National Trail Quality Standards for the South Downs Way: Key data: The percentage of each trail that is off-road (Measure no.3); Number of road crossings which need improvements to make safe Current position: 93.6 per cent of the South Downs Way is off-road; Improvements are needed to nine road crossings on the South Downs Way. Data source: South Downs National Park Authority (2010) Measuring Quality Standards on National Trails Full Survey, unpublished Responsibility for data collection: South Downs National Park Authority. Learning outside the classroom The National Park Authority will monitor changes in the percentage of schools visiting the National Park for educational purposes: Key data: Percentage of schools within 5km buffer using the South Downs National Park for Learning Outside the Classroom experiences at least once a year. Current position: Baseline data is being collected during 2012 as part of the schools audit of Our South Downs Project. Current baseline figures from TSE educational questionnaire (on a small sample size) is 69 per cent. Data Source: Tourism South East (2003/2004) TSE Education Questionnaire, Tourism South East; South Downs National Park Authority (2012) Our South Downs Project, SDNPA Responsibility for data collection: South Downs National Park Authority. Volunteer numbers The National Park Authority will monitor changes in the number of volunteers carrying out volunteer tasks across the National Park relevant to National Park purposes: Key data: Total number of people volunteering in the National Park in an area relevant to National Park purposes. Current position: There are currently 10,500 volunteers working in the National Park on an annual basis on tasks relevant to National Park purposes. Data source: South Downs National Park Authority (2012) Volunteer Audit: Resources for Change, SDNPA Responsibility for data collection: South Downs National Park Authority.

|

Footnotes

Click on the footnote number to take you back to your place in the document.

1 South Downs National Park Authority (2011) Special Qualities of the South Downs National Park, South Downs National Park Authority

2 Sustainable Development Commission (2008) Health, Place and Nature: How Outdoor Environments Influence Health and Well-being – A Knowledge Base, SDC

3 Ibid

4 The LHAs are Brighton and Hove City Council, East Sussex County Council, Hampshire County Council and West Sussex County Council

5 Accord for the Management of the Rights of Way and Access in the South Downs National Park, 2012. The signatories to the Accord are: the National Park Authority, Brighton and Hove City Council, East Sussex County Council, Hampshire County Council and West Sussex County Council

6 Quiet lanes are minor rural roads that are appropriate for use by walkers, cyclists, horse riders and other vehicles. (DfT Circular 02/2006)

7 Promoted routes are recreational routes, usually on public rights of way, specifically signed and promoted to attract users. They may be developed and promoted by the Local Highways Authorities, or by third parties, in partnership with LHAs, or independently

8 SDNPA (2012) Open Access in the South Downs: An Evaluation of Access Land, SDNPA

9 Tourism South East and Geoff Broom Associates (2004) Visitor Survey of the Proposed South Downs National Park, 2003–2004, Countryside Agency

10 South Downs Way People Counters at Old Winchester Hill Jan–July 2010

11 Tricia Butcher (2011) British Horse Society and Countryside Access Forum West Sussex,

West Sussex County Council

12 South Downs National Park Authority (2012) South Downs Way Events Listing, South Downs National Park Authority

13 Tourism South East and Geoff Broom Associates (2004) Visitor Survey of the Proposed South Downs National Park, 2003–2004, Countryside Agency

14 Environment Agency (2012) Recreation data based on WFD bodies, Environment Agency

15 The South Downs Visitor Survey 2011/2012 will be published in November 2012

16 Ibid

17 Department of Health Mental Health Division (2009) New Horizons, DoH

18 Defra (2010) National Parks Circular, Defra

19 South Downs National Park Authority and Natural England (2011) Access Network Mapping South Downs National Park and Adjacent Districts, SDNPA and Natural England

20 Kings College London (2011) LINE Benefits, Kings College London

21 Richard Louv (2005) Last Child in the Woods, Algonquin Book

22 Tourism South East and Geoff Broom Associates (2004) Visitor Survey of the Proposed South Downs National Park, 2003–2004, Countryside Agency

23 Defra (2010) National Park Circular, Defra

25 South Downs National Park Authority (2011) Events Review, SDNPA

26 South Downs National Park Authority (2012) Schools Database, SDNPA

27 Tourism South East (2004) South Downs National Park Visitor Survey Educational Use Questionnaire, and draft for 2011/12, Tourism South East

28 Learning Partnership Terms of Reference (October 2011)

29 South Downs National Park Authority (2011) Interpretation Audit of the South Downs National Park, SDNPA

30 South Downs National Park Authority (2011) Publications Audit, SDNPA

31 Tourism South East and Geoff Broom Associates (2004) Visitor Survey of the Proposed South Downs National Park 2003/2004, Countryside Agency

32 South Downs National Park Authority (2012) Volunteer Audit: Resources for Change, SDNPA

33 Ibid

34 South Downs National Park Authority (2012) South Downs Volunteer Audit: Resources for Change, SDNPA