Chapter 7

Well-conserved historical features and a rich cultural heritage

The distinct character of many areas of the South Downs National Park has been created by well-conserved historical features, some of which are rare and of national importance. Bronze Age barrows, Iron Age hill forts, Saxon and Norman churches, dew ponds, historic houses and landmarks of the two World Wars help to give the National Park strong links to its past human settlement. These links are reinforced by the variety of architectural building styles spanning the ages. Evidence of earlier farming traditions can still be seen today in the pattern of field boundaries, and relics of the industrial past remain in the form of old iron workings, brickworks, quarries and ancient coppiced woodlands.

The National Park has a rich cultural heritage of art, music and rural traditions. There is a strong association with well-known writers, poets, musicians and artists who have captured the essence of this most English of landscapes and drawn inspiration from the sense of place: Virginia Woolf, Jane Austen, Hilaire Belloc, Edward Thomas, Gilbert White, Edward Elgar, Joseph Turner, Eric Gill and Eric Ravilious, among many others. Today traditions continue through activities such as folk singing and events like Findon sheep fair. Culture lives on with new art and expression, celebrating the strong traditions of the past.1

The South Downs and Western Weald have an extremely rich cultural heritage illustrated in the density of features from all periods of history, a point which was explicitly recognised by English Heritage in its evidence to the Public Inquiry into the designation of the National Park.

Cultural heritage is one of the most important and treasured aspects of this National Park and includes the traditions of the communities living and working in it, as well as the work of creative people both past and present.

This chapter looks at important and distinctive features of the archaeology, listed buildings, heritage collections and significant cultural features of the National Park, and their condition. Some issues are better understood than others and so the report highlights the gaps in our knowledge.

Old Winchester Hill is an important Iron Age site © SDNPA/Anne Purkiss

|

Box 7.1 Cultural heritage of the South Downs National Park Key aspects of the National Park’s cultural heritage include: archaeological sites of the Bronze and Iron Ages; iconic villages and towns and their important features such as churches; early industrial sites from flint mines to ironworking furnaces; evidence of World War I and II; a varied range of historic buildings, often clustered in Conservation Areas designed parks and gardens; and artists, craft makers, scientists and thinkers inspired by this landscape. |

There is legal protection for some parts of the cultural heritage of the National Park, usually based on a test of importance of the site to the nation:

The most important archaeological sites are ‘scheduled monuments’.2

The most important buildings are ‘listed’.3

Areas of towns or villages can be designated as Conservation Areas’.4

Designed parks and gardens and battlefields can be registered.5

Archaeology

It is often said that the South Downs is particularly rich in prehistoric remains. Although it is difficult to assess whether their density per hectare exceeds those we might expect in other landscapes in south east England, there is no doubt that the signs of many previous civilisations are extremely prominent, on the open chalk in particular. Archaeological investigations have been carried out in the National Park for over 100 years, yet much probably remains to be discovered, especially in the more densely wooded areas between the River Arun and the A3. English Heritage has helped to develop regional ‘research agendas’, two of which (for the South East and the South) straddle the National Park. However, neither is complete, and an archaeological research agenda for the area within the National Park might well be developed by the Learning Partnership.

As the archaeology of the South Downs is very varied it is best to look at individual time periods, including the 2011 ‘Heritage at Risk’ entries.6

English Heritage – Heritage at Risk: www.english-heritage.org.uk/caring/heritage-at-risk/ and search for South Downs. |

Prehistory and Neolithic

The landscape provided food and shelter for hunter-gatherer peoples and the raw material for their flint tools. This low level of activity is known from the time of Boxgrove Man (around 500,000 years ago) until about 8000 years ago when people began to remove some of the tree cover.

With the coming of farming (the period known as the Neolithic), people started to mine flint to make tools on a much larger scale. They also built, for the first time, monuments that still stand in the landscape – in particular, hill-top ‘causewayed camps’.7 Both of these types of sites have been studied.

|

|

Key facts: Flint mines |

|

Flint mines in the South Downs are some of the most significant in England. |

|

|

Flint mines were the first industry in the National Park, some 6000 years ago. |

|

|

Heritage at Risk Register: Two flint mines within the National Park are listed as ‘Heritage at Risk’. |

|

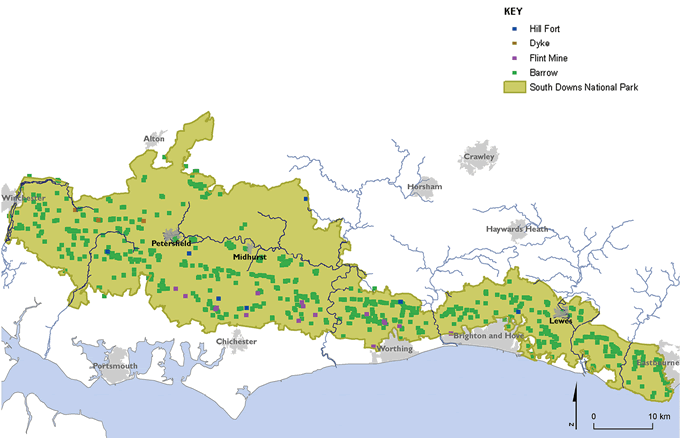

Map 7.1

Prehistoric sites in the National Park

Maps prepared by: GeoSpec, University of Brighton; February 2012.

Source: Historic Environment Records of Hampshire County Council, West Sussex County Council, East Sussex County Council, Chichester District Council and Winchester City Council, 2011

Ordnance Survey Crown Copyright © Licence No. 100050083.

Bronze Age

Metal tools are first found in the Bronze Age, about 4,000 years ago. At this time there was a great increase in farming on the chalk downs, in particular, accompanied by soil erosion and environmental change. It was in the Bronze Age that people started to build burial monuments, called barrows, sometimes as large groups or cemeteries.

|

|

Key facts: Barrows |

|

The barrows of the National Park are nationally important and the most significant barrow cemetery in the National Park is on Petersfield Heath. |

|

|

While some barrows are clustered on the South Downs Way they are also to be found on the chalk scarp and on the heathland of the Western Weald. |

|

|

Heritage at Risk Register: 33 of the Heritage at Risk sites in the National Park are Bronze Age in date and 30 of these are sites with one or more barrows. |

|

|

|

|

|

One of the Devil’s Jumps, a series of barrows near Treyford © Simon Burchill |

|

These early farmers have also left evidence of their settlements, hill-top enclosures, field systems and boundaries (known as cross-dykes). These sites are of national importance and have not been much studied as yet. Woodland cover in some parts of the National Park means aerial photographs are not effective and much more remains to be discovered. The ‘In The High Woods Project’ will use Light Detection And Ranging (LIDAR) technology to survey the densely wooded area between the A3 and the river Arun.

Iron Age

Iron Age hill fort – Old Winchester Hill © Commission Air

Iron Age inhabitants of the South Downs also farmed the landscape and large areas of field systems and settlements are known. The survival of such sites is unusual and so the sites are nationally significant. Earthwork systems such as the Chichester Entrenchments and sites in the woodland around Arundel are also very important and not yet very well understood.

|

|

Key facts: Iron Age sites at risk |

|

Heritage at Risk Register: Parts of the Chichester Entrenchments, the Caburn hillfort, two field systems and a settlement are on the Heritage at Risk register. |

|

Roman period

The first purpose-built road systems in the National Park were built by the Roman army to link coastal landing places with London. At intervals along the road there were places where travellers could get refreshments, stay overnight or change their horses – there is one in the National Park at Hardham and another at Iping. There are long stretches of these roads in the National Park and they are regionally important.

Within the National Park there are a number of large Roman farms (called ‘villas’) of which the most elaborate is Bignor Villa – a site that is nationally important for its rich mosaics. There are also very many smaller and more modest farmsteads and temples. Some sites are still being discovered. In some parts of the National Park the significant feature of the Roman period was industrial scale production, especially of pottery, at sites such as Alice Holt Forest and Wiggonholt.

‘Roman period’ – Mosaic at Bignor Roman Villa © Tupper Family

|

|

Key facts: Roman sites at risk |

|

Heritage at Risk Register: The Heritage at Risk register includes one stretch of Roman road, a temple site and a villa/farmstead in the National Park. |

|

Saxon period

Through place names, historical accounts and archaeology we know that the Saxon settlers came to the National Park from more than one part of north Europe. The main archaeological evidence of their lives comes from cemetery sites. Some of these cemeteries are of national significance and all are of regional importance because so few are known.

Very few rural Saxon settlements have been excavated and so we know little about their lives and farming activity but studies of place names show that many features in the landscape were named by people who spoke Saxon languages. The Saxon period also saw the first development of towns within the National Park with Lewes being occupied in the late Saxon period.

By the 9th century the minor kingdoms of Saxon England were being brought together, with King Alfred creating a system of defendable places (Burpham and Lewes within the National Park) to protect people, their livestock and valuables from the Viking raiders.

|

|

Key facts: Saxon sites at risk |

|

Heritage at Risk Register: There is only one Saxon site on the Heritage at Risk register. This is a cemetery site. |

|

Medieval

Following the Norman conquest of 1066, one of the first priorities was to establish Norman rule and a series of castles were built, including Arundel. The Battle of Lewes in 1264 was one of the key events in the War of the Barons which led to the first representative Parliament in England. The battle site is designated as a site of national significance.

All Saints Church, East Meon is one of a number of churches with nationally significant important medieval features © Adrian White

The evidence for the medieval use of the countryside can still be seen today. Areas of medieval royal or lordly hunts (such as Woolmer Forest) survive. The greensand soils were good for grazing and many still survive as commons. Other aspects of the landscape such as field hedges as boundaries, water meadows and river bridges survive in some places.

Many of the villages of the National Park have parish churches that were built soon after the Norman conquest. These churches were not just for prayer but were the centre of village life. In some cases the church is all that is left of a village, where people have moved or farming practices changed. Churches are a particularly significant part of the National Park’s cultural heritage with 167 parish churches being listed buildings. Some are particularly important because of their wall paintings and so are of national significance.

The demographic changes in the smaller settlements coupled with the national decline in attendance at church, is leaving communities struggling to raise funds to keep church buildings in good condition.

Churches and churchyards are also important habitats for some species (eg bats) and are also potential sites for learning about places, people, wildlife and geology.

|

|

Key facts: Medieval buildings at risk |

|

Heritage at Risk Register: While the Heritage At Risk register does not include any medieval archaeological site it does include six medieval buildings, four of which are churches. |

|

Post-medieval

England’s only Civil War included a battle at Cheriton and this battlefield is on the register of battlefields as of national significance.

The sale of monastic lands and properties by Henry VIII led to an increase in the number of estates owned by yeoman farmers and the aristocracy. This, together with a decline in the sport of deer hunting, led to the creation of many new parks and gardens. As fashions in garden design changed many were reshaped and important garden designers continued to work in the National Park area in the early 20th century including a number of Arts and Crafts gardens at King Edward VII hospital at Easebourne. There are 30 parks and gardens listed as being nationally significant and there are local lists researched by the two County Gardens Trusts8 that identify important sites local planning authorities can take account of.

Many of the larger parks and gardens were part of ‘great estates’ – owned and inherited by many generations of the same family. Such estate owners often owned lands in other parts of Britain and brought to the area new ideas on agricultural improvements, model farms and breeds of sheep and cattle to meet local conditions and maximise income. These estates were centred on great houses, many of which survive today – although sometimes in other uses or in the ownership of the National Trust.

The period after the 1540s saw many changes in religion within Britain and the growth of nonconformist churches and chapels, in particular after 1660. From 1830, it was again legal to build Roman Catholic churches. There are four Catholic churches that are listed buildings and one former Quaker meeting house – other nonconformist chapels are not currently listed.

Industrial history

The post-medieval industrial archaeology of the National Park has been studied in only the last 30 years or so. Raw materials dug from the Western Weald were used in iron and glass making industries which were nationally important in the medieval and Tudor periods. The casting of iron continued to be a local industry in Lewes into the 20th century. The other major industry seen in the landscape is the quarrying of chalk and sands. Some of these remains have been scheduled as being of national importance.

|

|

Key facts: Post-medieval sites at risk |

|

Heritage at Risk Register: There are two industrial archaeological sites, three buildings and two parks and gardens of the post-medieval period on the Register. |

|

Some of the chalk was burnt in lime kilns to produce lime for treating the soil or for making mortar and white bricks. Improving the soil was one aspect of the great agricultural improvements of the 18th century.

World War I and II

The nearby ports of Portsmouth and Southampton were very important for transporting troops and infrastructure to Europe and so large numbers of troops with their equipment camped and trained on the South Downs and on the heaths. There were also significant defensive installations along the coastline and valleys to guard against invasion and enemy aircraft. There are many signs of this history still in the landscape together with many photographs and recordings of people’s memories of these times. Twelve war memorials within the National Park are listed buildings. At present none of these sites has been scheduled.

Spitfires over the South Downs during World War II © Imperial War Museum

Buildings

Building materials

Historic buildings were usually constructed from materials quarried, gathered and hewn nearby. Roads were poor, especially in winter, and although boats were useful for shifting heavy materials such as stone, navigable rivers do not flow everywhere. Most people had no choice but to build with the materials they had near at hand, timber from the woods and forests of the weald, stone from local quarries and delves, flints gathered from the chalk downs and local clays won to mould bricks and tiles. This sheer variety of materials reflects the underlying geology of the landscape and is one of the great joys of the distinctive architecture of the National Park.

Lombard Street, Petworth © Anne Bone/SDNPA

Over time some of these sources became depleted. For example: hardwoods were in demand for charcoal-making and shipbuilding; and Scandinavian softwoods began to supplement them for construction in the 18th century. With the arrival of the railways, the predominance of the local roofing materials, clay tile, Horsham stone tiles and thatch, was challenged by the blue slates of North Wales. But unlike many parts of Britain, in rural Hampshire and Sussex these new sources of building material never entirely superseded the traditional choices. They often added yet another layer of diversity to the fascinating mix already in evidence.

Building designations

The relative importance of historic buildings is indicated by the grade of their listing.

The designation of listed buildings was first undertaken in the 1950s and 1960s and has been revised in more detail in almost all of the country, one of the exceptions being Sussex (including Brighton and Hove).9

Table 7.1 Listed buildings within the National Park*

|

Description |

No. in National Park |

|

Grade I |

152 |

|

Grade II* |

221 |

|

Grade II |

4,798 |

|

Total in National Park |

5,171 |

* One entry can include more than one building (and a building can be sub-divided during its use).

We would like to know about the historic building recording work by local groups and other organisations. We can use this to identify areas where there is no research or recording taking place. |

Farm buildings

There are 792 listed farm buildings10, including 424 farmhouses although not all of these buildings are necessarily being used now in farming. 11

|

Box 7.2 Types and current condition of listed buildings Grade I buildings of outstanding importance. Most of the Grade I buildings in the National Park are parish churches. Of the 12 buildings within the National Park on the Heritage At Risk register, four are Grade 1: Two of these are houses (or remains of houses), one is a church and one is the remains of a monastery. Grade II* buildings are of more than special interest. This group is primarily houses of varying scale. These buildings are fairly distributed evenly across the National Park area. There are six Grade II* buildings on the Heritage at Risk register – four are parish churches, one is a hospital chapel and one is the ruins of a former church. Grade II buildings are of special architectural or historical interest. Over three-quarters of this group are houses (including farmhouses). The remainder includes shops, barns, pubs and features such as dovecotes, telephone boxes and mills. Grade II buildings are located in almost every settlement across the National Park and there are large numbers in the four historic towns. Grade II sites are not included in the national Heritage at Risk register so the National Park Authority is commissioning a survey in 2012/13. This will then be the basis for measuring change in the condition of the listed buildings of the National Park. Some of the local authorities in the National Park area have had local lists of other important buildings which the National Park Authority has inherited. |

Schools

There are a number of listed school buildings in the National Park. The most important purpose-built school is Lancing College. Two other secondary and 10 primary schools use buildings that are listed. Schools have been an important part of the past usage of some stately homes, particularly during World War II. Some historic buildings now have a viable future as they are occupied by schools, such as Seaford College – which transferred to Lavington Park in 1946.

Houses

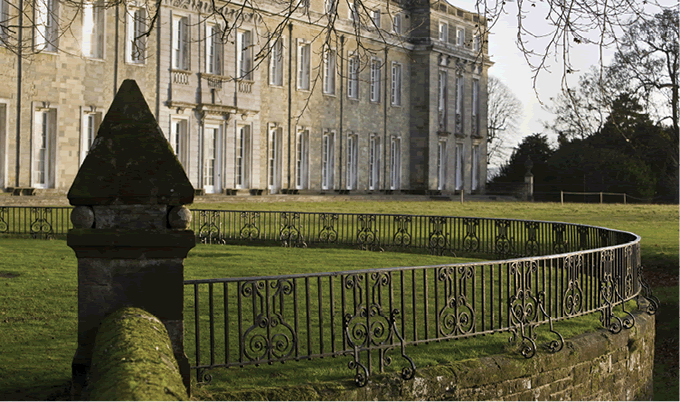

There are 48 listed ‘country houses’ which are the larger houses at the heart of estates. Some, such as Petworth House, would be viewed as ‘stately homes’ while others are more modest. Most are now managed as charitable trusts and some are open to the public.

Petworth House is one of the National Trust’s houses in the National Park and is especially significant for its art collections.

Most of the listed houses in the National Park are more homely in scale. In some parts of the National Park timber-framed houses are more common – this is especially notable in the Chichester District. This reflects the availability of timber as a building material on the wooded downs and in the Western Weald, and the survival of buildings from before 1800. There are 27212 timber-framed listed buildings in the National Park.

For more information on listed buildings visit http://list.english-heritage.org.uk |

Petworth House, Petworth © NTPL/David Levenson

Settlements

Each of the three historic market towns within the National Park – Petersfield, Midhurst and Lewes – has a distinctive character and a strong sense of place. All have large numbers of listed buildings and Conservation Areas (see below). Within these historic towns the design of new buildings, open spaces and infrastructure is important.

There are also many villages and hamlets within the National Park. Most villages have not been studied to find out how they have grown, apart from a group in Hampshire in a County Council supported study.13 As villages undertake local planning exercises it would be very useful to share the results and analyse them across the National Park.

We need data on villages and hamlets. |

The best measure of the significance of the historic parts of settlements is the existence of Conservation Areas. These are defined by the local planning authority and provide certain protections and constraints on change and development. To be effective, the designation of a Conservation Area should also include the development of an appraisal. To guide future changes, and to produce positive benefits, a Conservation Area Management Plan is required. Both should be updated once every ten years.

There are 166 Conservation Areas within the National Park, created by the local authorities before the National Park was in place. There are nine Conservation Areas on the Heritage at Risk register – all except one are in Hampshire. However, not all local authorities report on Conservation Areas at risk so this data may be skewed and missing in other places.

Heritage at risk

The annual national survey by English Heritage of the condition of heritage sites is called ‘Heritage at Risk’. (See Table 7.2 for 2011 figures and Key Data Box at the end of the chapter for further information). The National Park has been included in this report for the first time in 2011 and the results are summarised in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2 Heritage at risk†

|

|

Number in the National Park |

Number on Heritage at Risk register 2011 |

% of National Park sites at risk |

|

Scheduled Monuments |

616 |

50† |

8.1 |

|

Parks and Gardens |

30 |

2 |

6.7 |

|

Battlefields |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Listed Buildings: |

|

|

|

|

Grade 1 |

37 |

4† |

10.8 |

|

Grade II* |

203 |

5 |

2.46 |

|

Grade II |

4431 |

See note |

|

|

Conservation Areas |

166 |

9 |

5.42 |

|

Non-designated: |

|

|

|

|

Monuments |

7401 |

|

|

|

Find-spots |

6286 |

|

|

† Two scheduled monuments are also listed buildings so are double-counted in

this table.

Note: A survey of Grade II buildings is being undertaken in 2012/13 and this will allow the number that are ‘at risk’ to be identified for the first time.

Heritage collections

An important part of the heritage of the National Park is held in a variety of collections which are looked after, open to the public and used for research. This includes objects held by museums and art galleries, and archives held in record offices. The National Park has a number of ‘heritage sites’ that are open to visitors which preserve heritage and play an important role in tourism. Local residents and visitors can also experience the works of past authors, poets and composers at venues and festivals within the National Park.

The most important heritage collections are those that have been designated under a government scheme.14 There are also 34 heritage collections across the National Park under the national Accreditation Scheme including museums, archives and heritage sites. There is no monitoring of the condition of designated or accredited collections.

There are many other collections in museums, galleries, libraries and archives that hold works depicting the National Park.15

For more information on the collections. |

Other heritage sites

As mentioned elsewhere in the report, there are many other heritage sites open to visitors to the National Park, such as Petworth House.

For more information on other heritage sites. |

There are also heritage sites that are associated with famous writers, poets, natural historians, composers or artists, for example: Jane Austen House, Chawton; Gilbert White House and Oates Museum, Selborne and Charleston farmhouse, Firle.

Jane Austen’s House Museum at Chawton © Jane Austen’s House Museum

Conserving the historic environment

In the last 15 years there has been significant Heritage Lottery Fund investment in the historic environment of the National Park. This has included major capital schemes as well as community projects. A number of schemes are currently in development.

The agri-environment schemes (see Chapters 2 and 5) have also provided significant funding to take archaeological features out of cultivation and to conserve historic farmsteads.

English Heritage has undertaken a survey of the traditional building craft skills which shows there is a shortage of skilled people to maintain locally distinctive buildings.

Cultural life

Much of the cultural life of the South Downs and Western Weald is intimately connected to its landscapes, both real and imagined, and its sense of place.

“With 19th century urbanisation the rhythmically rolling Downs came to be regarded as peculiarly and beguilingly English, the landscape of dreams... In the English arts and crafts world the Downs had a special resonance and they became a major part of a national identity for an urban society with a taste for Old England, nostalgically harking back to a past rural idyll. For these various reasons the Downs became world renowned as a focus of English culture.’16

For these reasons, the National Park contains a great variety of cultural activity and this report can only record the most significant features. The National Park is a place of inspiration for composers, writers, musicians, poets and artists – there are so many that only the most significant are mentioned here:

Edward Elgar found fresh inspiration after the darkness of World War I and wrote the Cello concerto whilst living near Fittleworth.

The words to ‘Jerusalem’ are from one of the poems of William Blake, allegedly inspired by the view of the South Downs from Lavant.

Turner spent many summers at Petworth House where the Earl had a special studio built for him, to capture the best of the light.

Eric Gill was a leading artist who settled at Ditchling and attracted a community of other artists and craft makers.

The most important author associated with the National Park is Jane Austen, several of whose major works were written when she lived at Chawton.

There are three ‘cultural strategies’ within the National Park, developed by the three county councils. They are a useful summary of the priorities for cultural development in and beyond the area of the National Park.17

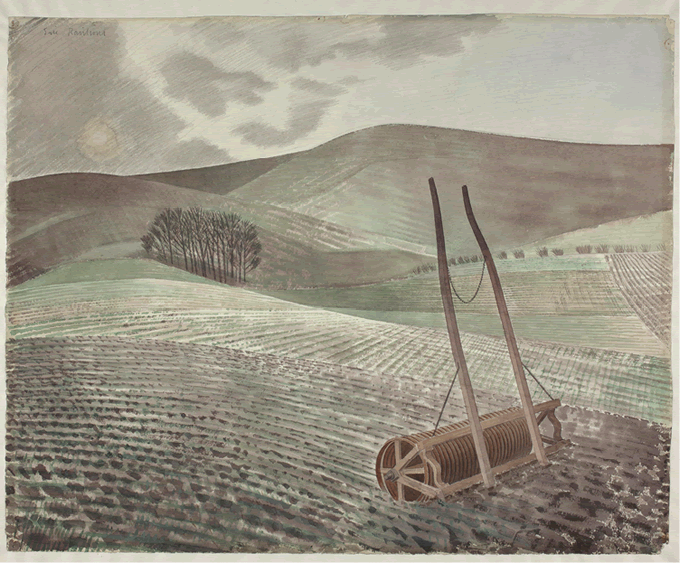

Eric Ravilious was often inspired by the Downs and many of his works are in the Towner at Eastbourne including the ‘Downs in Winter’ © Towner Art Gallery

Traditions

The long history of settlement of the South Downs and Western Weald has led to long-lived traditions. It is now hard to imagine how people lived – although literature such as Cold Comfort Farm can give us some idea of life on the South Downs in the 1930s.

The value of this area as a repository for tradition can be seen in the activities of folk music collectors such as the Broadwoods (an uncle and his niece who performed around Horsham) or classical musicians such as Ralph Vaughan Williams or Percy Grainger. Many folk songs were also collected from the travelling community at the Taro Fair in Petersfield. While some songs continued as living traditions in families such as the Coppers (once shepherds and later publicans) others have been captured on recordings or transcribed as sheet music and so are available to singers today. Maintaining a body of people who know and sing traditional songs is the aim of the ‘Songs of the South Downs’ project.18

Throughout the nation bonfire night is still marked traditionally with bonfires and fireworks – but the best known celebration is undoubtedly Lewes, attended by up to 60,000 people.

Traditionally the agricultural year was marked by a series of events linked to the farming year and to the need to buy and sell produce and hire labour. The Taro Fair in Petersfield was started in 1820 as a cattle fair but became the biggest horse-selling fair in south-east England in the 1920s and 1930s. Traditional fairs still continue in other towns. Ebernoe’s Horn Fair was revived as a tradition in 1865 and is held annually when, after a cricket match, the best cricketer is given the horns from the sheep being roasted for the feast that closes the day’s events.

An important part of English rural life that started in the area is the Women’s Institute which campaigned to raise the quality of life in rural areas. Its first meeting in England was in the village of Charlton, West Sussex in 1915.

|

Key data: Well-conserved historical features and a rich cultural heritage Listed buildings and archaeology sites The National Park Authority, working with our partners, will monitor listed buildings and archaeology sites. Heritage information is held as a database called the Historic Environment Record (HER) by local authorities. Information has been compiled to the National Park boundary. Every year English Heritage compiles a report on the sites that are ‘At Risk’ of loss of their historic information or fabric – this is primarily compiled from reports received and so may not include all sites at risk. No Grade II buildings are included in this survey which is a major gap in our knowledge. Conservation Areas are reported at the discretion of local authorities but as not all councils have officers doing this work it may not represent the whole picture. It will be possible to monitor the number of sites that are ‘At Risk’ each year and so this can be an indicator of the extent to which the historic environment is ‘well conserved’: Key data: Heritage at Risk. Current position: As in Table 7.2 ‘Heritage at Risk’. Data source: English Heritage (2011) Heritage at Risk, English Heritage Responsibility for data collection: English Heritage and local authorities. Taking part in cultural heritage The National Park Authority, working with our partners, will monitor participation in cultural activities. There is a national survey called ‘Taking Part’, run for the Dept of Culture, Media and Sport, which attempts to calculate how many people visit museums or attend arts events. It is broken down by district/borough council area and cannot therefore easily be adjusted to National Park boundaries. Currently there is no count of the number of people engaged in the cultural heritage of the National Park. This would include people visiting sites and events, taking part in projects, the membership of local societies, or learning activities and volunteering: Key data: Involvement in cultural heritage activities. Current position: Unknown. Gathering all this information would be a very useful exercise but will require assistance and support from a variety of groups and organisations – assistance would be gratefully received.

|

Footnotes

Click on the footnote number to take you back to your place in the document.

1 South Downs National Park Authority (2011) Special Qualities of the South Downs National Park, SDNPA

2 Covered by the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979

4 Ibid

5 These heritage assets are not protected under an Act of Parliament but are a ‘material consideration’ in any planning application

6 It is important to note that Heritage at Risk does not consider future threats although we already know that coastal erosion is destroying the archaeology in those parts of the National Park

7 Large enclosed areas that are probably not defensive sites as the ditch is not continuous

8 The National Park is served by the Sussex Gardens Trust (see www.sussexgardenstrust.org.uk) and the Hampshire Gardens Trust (see www.hgt.org.uk). Both are voluntary organisations that help to conserve and increase understanding of these important assets. They also advise owners and comment on planning applications

9 The Sussex lists are accepted by English Heritage as not being of the same quality as Hampshire – English Heritage now prefers to revise the lists in areas smaller than a whole county and where the need is greatest

10 For more information on listed buildings visit the English Heritage website

http://list.english-heritage.org.uk

11 The four historic towns are Petersfield, Midhurst, Petworth and Lewes. These towns are defined as ‘historic’ by English Heritage and were all included in a national programme known as ‘Extensive Urban Surveys’. These surveys help to inform our understanding and are an important tool in considering planning applications in these towns

12 Ibid

13 Hampshire County Council/Bournemouth University, The Historical Rural Settlement Study, Unpublished study

14 Hampshire Record Office (Winchester) – for its entire holdings; Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton and Hove – four collections designated but the relevant one is the Booth Museum of Natural History; and Weald & Downland Open Air Museum – for its entire holdings.; MLA ‘Designated Collections List

15 The Towner gallery at Eastbourne has important collections of landscape inspired works and Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. Archaeological collections are held at Winchester City; Hampshire County including Alton; Chichester District; Worthing; Horsham; Brighton; and Museum of Sussex Archaeology, Lewes. Booth Museum, Brighton; and Hampshire County Museum service

16 Brandon, P (1998) The South Downs, Phillimore and Co Ltd

17 County Cultural Strategies/Sustainable/Hampshire County Council (2008) Sustainable Communities Strategy 2008–2018; West Sussex County Council Cultural Strategy 2009–2014; East Sussex County Council Cultural Strategy 2008, Hampshire County Council

18 The South Downs Songs Project is run by The South Downs Society. Workshops explore different themes e.g. love and work, and set them in their historical context