Chapter 4

A rich variety of wildlife and habitats including rare and internationally important species

The unique combination of geology and micro-climates of the South Downs has created a rich mosaic of habitats that supports many rare and internationally important wildlife species. Sheep-grazed downland is the iconic habitat of the chalk landscape. Here you can find rare plants such as the round-headed rampion, orchids ranging from the burnt orchid and early spider orchid to autumn lady’s tresses, and butterflies including the Adonis blue and chalkhill blue.

The greensand of the Western Weald contains important lowland heathland habitats including the internationally designated Woolmer Forest, the only site in the British Isles where all our native reptile and amphibian species are found. There are large areas of ancient woodland, for example, the yew woodlands of Kingley Vale and the magnificent ‘hanging’ woodlands of the Hampshire Hangers.

The extensive farmland habitats of the South Downs are important for many species of wildlife, including rare arable wildflowers and nationally declining farmland birds. Corn bunting, skylark, lapwing, yellowhammer and grey partridge are notable examples.

The river valleys intersecting the South Downs support wetland habitats and a wealth of birdlife, notably at Pulborough Brooks. Many fish, amphibians and invertebrates thrive in the clear chalk streams of the Meon and Itchen in Hampshire where elusive wild mammals such as otter and water vole may also be spotted. The extensive chalk sea cliffs and shoreline in the east host a wide range of coastal wildlife including breeding colonies of seabirds such as kittiwakes and fulmars.1

In the past, conservation effort has often focused on specific species, habitats and sites. This approach has been partially successful with targeted conservation efforts turning around the fate of many species and extensive new areas of habitat being created. However, other species and habitats have continued to decline both nationally2 and within the National Park.3

The Natural Environment White Paper for England (2011)4 is based on the principle that nature is often taken for granted and undervalued, but that people cannot do without the benefits and services it provides, and advocates a landscape-scale approach to conservation. The Water Framework Directive5 supports this call for a landscape-scale approach to the conservation of wildlife and habitats.

In 2008, a wide consultation was held in the south east to develop a landscape-scale approach to conservation by identifying ‘Biodiversity Opportunity Areas’ (BOAs).6 BOAs were selected for their potential for wildlife enhancement and for their potential to create a good ecological network for the region. Nearly half (46 per cent) of the National Park is covered by BOAs.

There are a large number of other biodiversity-led landscape initiatives in or being developed for the National Park including:

The South Downs Way Ahead Nature Improvement Area (NIA) – a chalk grassland focused project;

Arun and Rother Connections – a wetland project;

South Downs Wooded Heaths Partnership – a heathland project;

West Weald Landscape Partnership – a woodland project;

Local Nature Partnerships (LNPs) for Hampshire and Sussex;

Local Wildlife Sites Partnerships (e.g. West Sussex);

Local Rivers Trusts; and

Water Framework Directive projects e.g. Adur and Ouse.

Farming and forestry have shaped the wildlife and habitats of the area for thousands of years, and have been instrumental in creating and maintaining the area’s special qualities. For example, chalk downland – perhaps the most iconic habitat of the National Park – owes its existence to centuries of sheep farming.

However, the needs of land managers and wildlife do not always align. Changes in the economy, agricultural policy and the application of new technologies resulted in more intensive agriculture in recent decades which has had a devastating impact on many farmland species.

It’s not all bad news though – in recent years targeted conservation efforts, sensitive land management and landscape-scale coordination have led to the recovery of some of the special wildlife and habitats of the South Downs.

While we have reasonably good data for land covered by agri-environment schemes and England Woodland Grant Schemes (EWGS), there is a significant lack of data on wildlife and habitats for farmland not under environmental land management agreements. This data gap could be partially addressed by targeted species and habitat monitoring work, for example, bat surveys.

|

We need data on targeted species and habitats. |

|

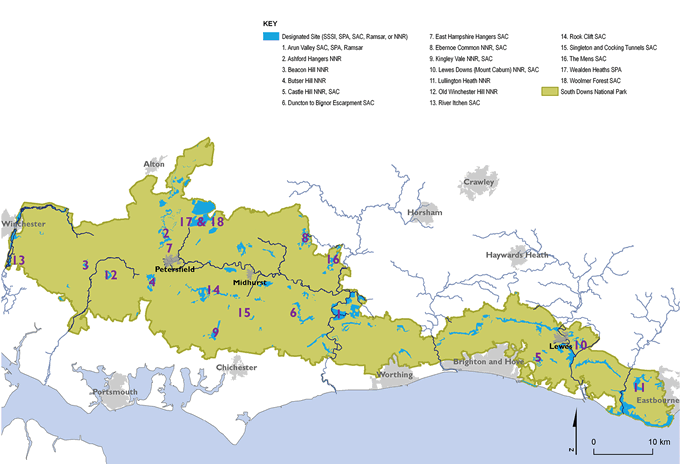

Box 4.1 Jewels in the crown of the South Downs The National Park has a very high density of sites designated for their wildlife value: 1. The Arun Valley is designated as a RAMSAR site, a wetland of global importance. This site is of outstanding importance for its wintering waterfowl, breeding waders, rare wetland invertebrates and scarce plants. 2. There are 13 Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) in the National Park, which are protected by UK and EU legislation. Woolmer Forest SAC is the only site in England which is home to all of our native species of reptiles and amphibians. Two of the SACs in the National Park are also designated as European Special Protection Areas (SPAs) for their international importance for birds. All the SACs and SPAs in the National Park are also designated as SSSIs. 3. There are also nine National Nature Reserves (NNRs)7 within the National Park, which are sites of national importance for their biodiversity value. All of these are also designated as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). Examples of NNRs are Castle Hill NNR near Brighton, an outstanding area of chalk downland, and Kingley Vale NNR, one of Europe’s finest yew forests. 4. In total, there are 86 SSSIs in the National Park (covering 6 per cent of the area). 5. 853 sites (9 per cent of the National Park area) are locally designated wildlife sites described as either Local Wildlife Sites, Sites of Nature Conservation Importance (SNCIs) or Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs). |

Table 4.1 Designated sites within the National Park

|

Designation |

No. of sites wholly/partly within National Park |

Area within National |

|

Ramsar Sites |

1 |

530.4 |

|

Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) |

13 |

2,782.6 |

|

Special Protection Areas (SPA) |

2 |

1,715.8 |

|

National Nature Reserves (NNR) |

9 |

840.1 |

|

Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)8 |

86 |

9,945.5 |

|

Local Wildlife Sites (SINC/SNCI) |

853 |

14,279.4 |

Map 4.1

Distribution of designated wildlife sites of national and/or international importance, within the National Park

Maps prepared by: GeoSpec, University of Brighton; April 2012.

Source: Natural England, 2011

Ordnance Survey Crown Copyright © Licence No. 100050083.

Habitats

The National Park has an incredibly rich and diverse array of wildlife habitats, many of which are recognised as national and European priorities for wildlife.

A large percentage of the National Park is classified as farmland, which includes important wildlife habitats such as unimproved and semi-improved grassland, arable land and hedgerows. Farmland habitats support populations of many native species, including some which are rare and threatened such as grey partridge and corn marigold. Heathland habitats in the National Park are also very important for wildlife, supporting distinctive plant communities and heathland specialists, for example, the silver-studded blue butterfly.

During World War II many of the chalk grassland sites in the South Downs were ploughed and have since remained in cultivation. West of the River Arun, where the National Park is more wooded, there are important features such as the ‘hanger’ woodlands of the steep escarpments. Woodland habitats are recognised for their biodiversity value and often support specialist species such as the barbastelle bat and our native bluebell.

In addition to their biodiversity benefits, the wildlife habitats of the National Park provide a wide range of other benefits such as recreational and educational opportunities, tranquillity and economic returns.

|

|

Key facts: Wildlife habitats |

|

Farmland habitats (85 per cent – this includes some woodland, arable, hedgerows and other habitats) |

|

|

Chalk grassland (4 per cent) |

|

|

Lowland heath (1 per cent) |

|

|

Woodland (23.8 per cent) – approximately half of which is ancient woodland) |

|

|

Floodplain grazing marsh (1.5 per cent) |

|

|

Rivers and streams (321km of main river) |

|

|

Coastal and marine habitats (6.7km2, including 20km of coastline) |

|

|

Urban habitats |

|

|

Levin Down © Mark Monk-Terry/Sussex Wildlife Trust |

|

Chalk grassland

Chalk grassland is one of the priority habitats of the South Downs, covering 5,608ha of the National Park (4 per cent). It is often referred to as the European equivalent of tropical rainforest due to the rich diversity of species it supports. However, chalk grassland has suffered badly from loss and fragmentation both nationally and within the National Park.9

|

|

Key facts: Chalk grassland |

|

36 per cent of the chalk grassland sites within the National Park are less than 1ha in size. |

|

|

Only 45 chalk grassland sites are over 10ha in size. |

|

|

Only 45 per cent of chalk grassland in the National Park is designated as SSSI, meaning that over half does not benefit from significant legal protection. |

|

|

Malling Down © Neil Fletcher/Sussex Wildlife Trust |

|

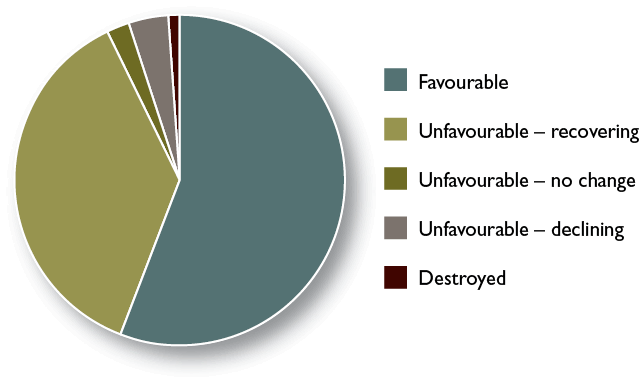

Figure 4.1 Chalk grassland SSSI units in the National Park

Source: Natural England (2012) England SSSI Unit Condition Assessments, Natural England. Analysis by Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre

Heathland

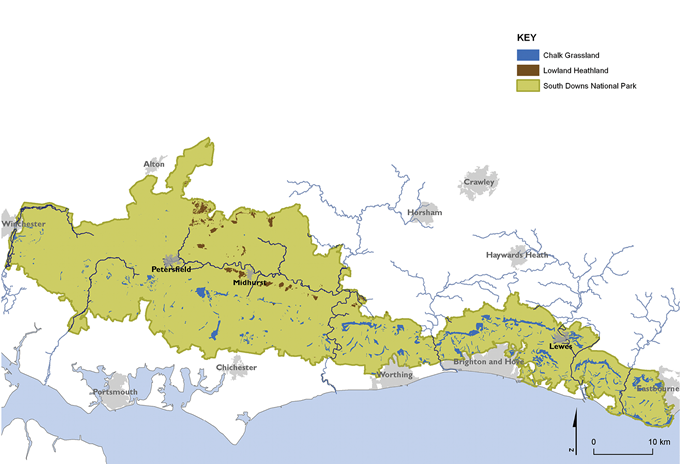

Heathland is another national priority habitat found within the National Park. Heathlands are of considerable international biodiversity importance. However, they are very vulnerable to rapid loss and degradation, for example, through neglect. Lowland heathlands are confined to the western margins of north-west Europe and have suffered dramatic losses in recent decades. Map 4.2 shows heathland distribution in the National Park.

There are several different types of heathland habitat, including wooded heath and chalk heath. Chalk heath is a particularly rare habitat type; Lullington Heath National Nature Reserve near Eastbourne is one of the largest areas of chalk heath in Britain.

Map 4.2

Chalk grassland and lowland heathland distribution within the South Downs National Park

Maps prepared by: GeoSpec, University of Brighton; February 2012.

Source: Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre and Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre, 2011

Ordnance Survey Crown Copyright © Licence No. 100050083.

|

|

Key facts: Heathland |

|

Over 95 per cent of lowland heathlands have been lost globally. |

|

|

There is 1,544ha of lowland heathland remaining within the National Park, which represents an important international resource. |

|

|

Just over half (55 per cent) of the heathland within the National Park is designated as SSSI. |

|

|

Graffham Common © Miles Davis/Sussex Wildlife Trust |

|

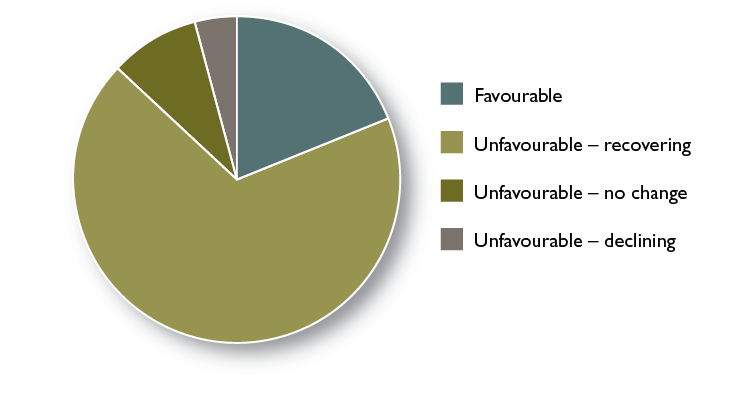

Figure 4.2 Heathland SSSI units in the National Park

Source: Natural England (2012) England SSSI Unit Condition Assessments, Natural England. Analysis by Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre

Ancient woodland

Ancient woodland is a nationally important and threatened habitat, and its existence over hundreds of years has preserved irreplaceable ecological and historical features.10 Ancient woodland in the National Park includes a few surviving remnants of large-leaved lime woodland, which may closely resemble the post-glacial ‘wildwood’ that covered the South Downs prior to Neolithic forest clearance some 6,000 years ago.11 This valuable resource is increasingly under threat from development pressure and lack of appropriate management.

|

|

Key facts: Ancient woodland |

|

Ancient woodland covers 17,351ha within the National Park – more than five times the national average.12 |

|

|

The spread of woodland cover across the National Park is uneven, with the west being significantly more wooded than the east. |

|

|

The condition of ancient woodland sites is not well known, apart from those cases where woodland forms part or all of an SSSI (only 8 per cent of the ancient woodland resource within the National Park), but 70 per cent of the ancient woodland within SSSIs is considered to be in favourable condition. |

|

|

Ancient yews at Kingley Vale © www.jamesgilesphotography.co.uk |

|

Woodland habitats of particular value for biodiversity within the National Park include:

‘hanger’ woodlands (which cling to steep greensand and chalk slopes);

yew forests (for example, Kingley Vale);

ancient wood pasture (for example, Ebernoe Common near Petworth);

wooded heaths (for example, Blackdown near Haslemere);

‘rews and shaws’ (linear strips of ancient woodland along field edges and streams); and

‘veteran’ trees.

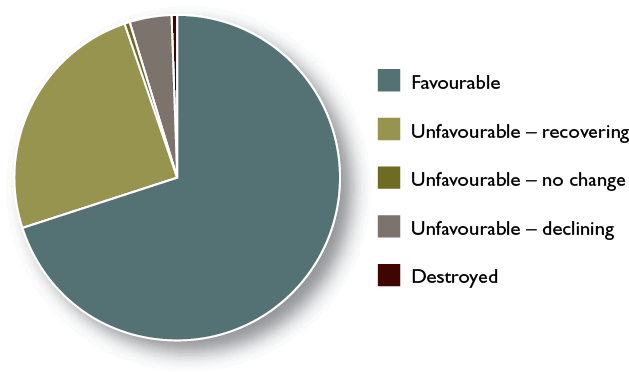

Figure 4.3 Ancient woodland SSSI units in the National Park

Source: Natural England (2012) England SSSI Unit Condition Assessments, Natural England. Analysis by Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre

|

Case Study Michael Prior

Michael Prior is Head Forester at Stansted Park in West Sussex which was a joint winner of the Duke of Cornwall Award for Multi-purpose Woodlands in 2010. In 1983 the 10th Earl of Bessborough gifted the estate to the Stansted Park Foundation which is tasked with managing the estate for the benefit of the nation in perpetuity. “We have 464ha of woodlands on the estate, virtually all of which is classed as either Ancient Semi-natural Woodland or Plantation on Ancient Woodland Sites. Our trees range from commercial conifers through worked sweet chestnut and hazel coppice to old broadleaf woodland. The forest is bisected by large open vistas which are major features of the Grade 1 listed Park and are managed under the Higher Level Stewardship Scheme along with other parkland features. The forest is entered into the English Woodland Grant Scheme (EWGS) and our management focuses on producing sustainable timber at the same time as restoring landscape, conserving wildlife and managing extensive public access. Wherever possible we work to produce saleable woodland products from across all the different woods. Profits are returned to the Foundation, helping to support this work. I believe the biggest threat to woodland is lack of management. The restoration of derelict woodland within the National Park could bring many benefits, helping to produce utilisable timber and stimulating the local economy.” |

Farmland

Farmland includes wildlife habitats such as grassland, arable land and hedgerows. The quality of farmland habitats for wildlife can vary enormously, ranging from species-rich unimproved grasslands to intensively managed grasslands which support very little wildlife.

Diverse farmland near Firle © Amanda Davey

Arable cropland is a great place to see some of the UK’s rarest farmland birds. These include corn bunting, grey partridge, skylark and stone curlew. The National Park is also considered to be a national hotspot for rare arable plants. In addition to plants and birds, farmland habitats also support some interesting and special mammals such as harvest mouse and brown hare. Farm hedges and field margins act as ‘wildlife corridors’ for many species including bats.

While the extent of farmland has probably not changed significantly over the past century, the balance of different uses has varied a great deal, and over the last 50–100 years the quality of many farmland habitats for wildlife has declined dramatically. Increasing intensification of agriculture as a result of farming subsidies in the latter half of the 20th century had a devastating impact upon many species of wildlife dependent on farmland habitats. For example, modern herbicides and seed cleaning methods reduced the presence of arable plants such as rough poppy, and changes in arable cropping practices such as a switch from spring to autumn sown cereals has reduced habitat and food availability for farmland birds and other wildlife. Proportions of different habitats which make up farmland have also changed in recent history, for example, significant amounts of sheep-grazed chalk downland were ploughed up during and after World War II to grow crops such as wheat and barley, and over the past decade vineyards have increased in number.

Rough poppy and corn marigold © Natural England

Over the past decade or so, agri-environment schemes have helped to address declines in some farmland species. There is extensive data on farmland habitats (extent, condition and management activities) for farmland under agri-environment agreements. Some wildlife species data for farmland sites is collected by landowners, volunteers and conservation organisations.

|

We need data on wildlife and habitats for farmland not under environmental land management agreements. |

Rivers and streams

The rivers and streams of the National Park support a rich and diverse array of habitats and species. Wildlife habitats adjacent to rivers and streams include semi-natural riparian vegetation, wet woodland and wet grassland, supporting invertebrates, riverine bird species and also populations of mammals such as water shrew, otter and water vole. The fish species in these rivers and streams include salmon, brown trout, bullhead, European eel and brook lamprey:

Many of the rivers in the National Park, such as the Arun, the Rother, and the Ouse, support important fish nurseries. However, the fish populations of the rivers (the Itchen, in particular), have been modified by introductions of farm reared trout and the removal of other species.13

The chalk streams of the National Park are also very important for their biodiversity value – a recent survey by Nigel Holmes14 stated that Sussex has some of the finest examples of natural chalk stream habitats in the country.

‘Flashy rivers’ such as the Ouse and Cuckmere support ecological communities associated with clay dominated lowland rivers including good populations of fish such as brown trout, roach, pike, rudd, bream, tench, perch, bullhead, stone loach, minnow, brook lamprey and European eel. They are also home to a wide range of other species.

Other freshwater habitats in the National Park important for their wildlife value include lakes, reedbeds, ponds (for example, dewponds), canals and freshwater grazing marsh.

Brown trout © Sussex Wildlife Trust

The ‘ecological status’ of UK rivers and streams is assessed under the Water Framework Directive15 (along with groundwater status and quality). More information can be found in the Water Fact File.

|

Case Study Fran Southgate

Fran Southgate is the Wetlands Officer for Sussex Wildlife Trust. Her role includes providing free advice on ways of restoring wetlands and improving water resources across the county. “Fresh water is one of our most valuable natural resources. In the south east of England too many people have taken too much water from our environment, and many wetlands and their wildlife have suffered significant declines as a result. Our wetlands are finally being recognised for their true value, providing us with fuel, flood storage, food, clean water, fertile soils and other valuable environmental ‘services’. Wherever possible, we are taking steps to safeguard and restore them. Surface wetlands such as ponds are important in the National Park because most water seeps through the naturally porous chalk into aquifers. We support the restoration and re-creation of wetlands wherever viable, as well as working with partners such as the South Downs National Park Authority to identify some of our rarest wetland habitats. Our recent study of chalk streams in Sussex mapped more than 135km of this internationally rare habitat – evidence that will help us all to protect these precious wetlands in the long term. We are also working with local people to tackle bigger wetland issues such as climate change, flooding and drought. In April 2012, the Arun and Rother Connections (ARC) Partnership secured funding to pay for landscape scale wetland restoration work and community engagement around these two major rivers. The Partnership hopes to tackle issues such as the spread of non-native invasive species like giant hogweed and Australian swamp stonecrop, which have caused significant damage to our native wildlife and to local tourism and farming. In the long term, we hope that this work will bring people closer to their local freshwater environment, improve and expand wetland habitats such as fen and reedbed, and promote recovery of some of the National Park’s rarer wetland species such as water vole and the dazzling common club-tail dragonfly.” |

Coastal and marine

Coastal and marine habitats make up a relatively small proportion of the National Park. However, they are very important for their landscape, biodiversity and cultural value. Activities such as fishing and navigational and marine aggregate dredging have had negative impacts on coastal and marine biodiversity, but focus on conservation work in recent years has helped to safeguard some marine species and habitats.

|

|

Key facts: Coastal and marine |

|

Beachy Head cliffs © Eastbourne Tourism Department |

|

|

The coastal habitats within the National Park include maritime cliffs and slopes and saline lagoons. |

|

|

The principal marine and estuarine habitats in the National Park include: |

|

|

coastal saltmarsh; |

|

|

intertidal rock (including intertidal chalk); and |

|

|

intertidal sediment (predominantly shingle). Examples of coastal and marine plant species are: |

|

|

hoary stock; |

|

|

rock sea-lavender; and |

|

|

sea-heath. |

|

|

Breeding birds found in these habitats include: fulmars; kittiwakes; and peregrines. |

|

|

Between Seaford and Beachy Head there are surviving areas of clifftop chalk heath, a very rare habitat type. |

|

|

The chalk cliffs are in a constant state of erosion, but this does not have a significant impact on their importance for biodiversity as there is no net loss of habitat. |

|

|

The shingle in the Seaford to Beachy Head SSSI supports a distinctive flora with species such as curled dock, sea beet, yellow horned-poppy and sea bindweed. The shingle bank habitat supports a number of uncommon centipedes, some of which have not been recorded anywhere else in the UK. |

|

|

There are some saline lagoons within the National Park; these shallow areas of brackish water are home to a wide range of invertebrates and other wildlife. |

|

Fulmar © Sussex Wildlife Trust

The National Park contains four coastal plain estuaries: the Arun, Adur, Ouse and Cuckmere. Of these, only the full extent of the Cuckmere estuary is within the National Park boundary. Estuarine habitats host a diversity of species including migrant species such as European eel and sea trout. Saltmarsh habitat can be found in all four estuaries although in fairly small patches. The former meanders of the estuaries and the surrounding brackish and freshwater marshes support many rare and scarce invertebrates as well as regionally important amphibian populations, such as the common toad. These, in turn, support populations of breeding birds including nationally important populations of migrant birds. Saltmarsh habitat has declined significantly in the UK over the 20th century mainly due to draining of estuaries to support port development and urban expansion.

Intertidal wave-cut chalk platforms occur along a 22km stretch of shore from Beachy Head westwards to Seaford Head, and from Newhaven to Brighton marina (of which approximately 12km is in the National Park). A rich variety of seaweed is found in the mid-shore zone, together with mussels, limpets, periwinkles and barnacles. Certain algae, which are present in damp, shady places within caves at the base of the chalk cliffs, are rare or threatened. Species of interest include the burrowing piddock, the squat lobster and the sea urchin Psammechinus miliaris.

Squat lobster © Rohan Holt

Species

The National Park supports a wealth of wildlife including iconic species such as burnt orchid, round-headed rampion, otter, skylark, barn owl and brown trout. It is also home to less well-known species such as the barbastelle bat, the chalk carpet moth and sundew (a carnivorous plant).

Many of the species found in the National Park are rare and localised: for example, the greater mouse-eared bat. The National Park and Bognor Regis are the only places in the UK where this species has been recently recorded. The last known British colony disappeared in 1985, however a single male was discovered in the National Park in 2002 and has been recorded at the same location every year since.

%20Simon%20Colmer_fmt.png)

Sundew © Sussex Wildlife Trust

Rare species are often restricted to habitats which are also rare. Populations of some species, such as the Adonis blue butterfly, have recently shown signs of recovery in the National Park as a result of conservation efforts and sensitive land management. In addition, some species are benefiting from climate change by extending their distribution and the range of habitats they are able to utilise – the silver-spotted skipper butterfly is a good example of this.

|

Box 4.2 Habitat specialist species |

|

Examples of species which are habitat specialists: |

|

arable plants such as corn marigold; |

|

bee orchid (chalk downland); |

|

Adonis blue butterfly (chalk downland); |

|

purple emperor butterfly (broadleaved woodland); and |

|

nightjar (heathland and open woodland with clearings). |

|

Bee orchid © Sussex Wildlife Trust |

|

Box 4.3 Invasive species A significant cause of decline for some of our native wildlife and habitats is the spread of invasive non-native species. These are exotic species which have been introduced (either deliberately or by accident) into our countryside. Invasive non-native species are now regarded as the second greatest threat to global biodiversity after habitat loss and they are causing significant problems for a wide range of species and habitats across the National Park, for example: Water vole populations across the National Park have been devastated by American mink. Himalayan balsam, Japanese knotweed and giant hogweed are examples of some of the invasive, non-native plant species which are contributing to the decline of native wildlife and habitats. Many invasive species are expensive and difficult to control – and in some cases, such as the signal crayfish, populations are almost impossible to eradicate once established. |

|

We need data on the distribution and density of many invasive non-native species. |

The most common and widespread invasive species are often found in wetland habitats, for example, a recent survey of the Arun and Rother river catchments showed that the problem of invasive, non-native species such as Himalayan balsam and giant hogweed was far greater than originally predicted. In woodland and heathland habitats Rhododendron ponticum is among the most widespread and damaging invasive species.

We have good baseline and trend data for many native species thanks to the work of many organisations, individuals and volunteers. Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre (HBIC) and Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre (SxBRC) play a key role in generating, collating and analysing biodiversity data for the National Park.

We have relatively comprehensive datasets for some groups of species such as birds and butterflies.

|

We need more data on some other species groups such as fungi. |

The following species datasets have been selected to monitor for this report (and subsequent editions) due to comprehensive baseline data, the existence of standard monitoring schemes for these species, association with different priority habitat types, potential to act as flagship species and potential to act as environmental indicators.

|

Key data: A rich variety of wildlife and habitats including rare and internationally important species Biodiversity-led landscape initiatives It can be difficult to gather and analyse meaningful data to monitor the success of biodiversity conservation at the landscape scale. However, some species (or species groups) are considered to be good environmental indicators of landscape quality and connectivity. Bats and the Duke of Burgundy butterfly have been selected as appropriate indicators of landscape-scale activity for the South Downs National Park as they are national landscape-scale indicators for Defra and Butterfly Conservation respectively. Key data: Bat populations (Defra bat index) and Duke of Burgundy butterfly populations will be monitored as indicators of landscape-scale conservation. Current position: The Defra bat index measures national population changes in six widespread bat species. Bat populations experienced major declines both nationally and in the National Park during the latter half of the 20th century. However, since 2000, bat populations in England have increased by 21 per cent. The Duke of Burgundy is one of Britain’s fastest declining butterflies, having declined nationally by nearly 50 per cent over the past 10 years. However the National Park is one of our national strongholds for this rare butterfly, and has some of the largest remaining colonies in the country (e.g. at Butser Hill). Data source: Butterfly Conservation, National Bat Monitoring Programme, Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre and Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre Responsibility for data collation: Bat Conservation Trust, Butterfly Conservation, Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre and Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre. Farmland Birds Key data: Defra national Farmland Bird Index. Current position: Breeding farmland bird populations in the UK are at their lowest levels ever recorded, at half of what they were in 1970. Most of the declines occurred between the late seventies and the early nineties, but there has also been a national decline of 9.4 per cent overall in the last five years (Defra Biodiversity Indicators 2011). There is currently insufficient data to estimate breeding farmland bird populations and trends for the National Park accurately.

This data gap can be addressed by identifying and monitoring more survey sites in the area. Data source: Defra (2011) Wild Bird Populations in Britain 1970–2010, Defra Responsibility for data collection: Defra/RSPB/British Trust for Ornithology. Local wildlife sites Key data: A local authority single dataset indicator for the condition of Local Wildlife Sites has been adopted by local authorities across the National Park. Current position: In total there are 861 Local Wildlife Sites (SNCIs/SINCs) within the National Park. Of these, 47 per cent (408) are assessed as being in positive conservation management, 9 per cent (77) are not in positive management, and the management is unknown for 44 per cent (381). Data source: Hampshire, East Sussex and West Sussex County Council and Brighton and Hove City Council Responsibility for data collection: Local authorities. Condition of protected sites Key data: Condition of SSSI. Current position: 48.8 per cent of the SSSI units in the National Park are assessed as being in favourable condition (compared to a national average of 44.9 per cent), and 38.7 per cent are assessed as unfavourable but recovering (compared to 30.6 per cent nationally). Data source: Natural England (2012) England SSSI Unit Condition Assessments, Natural England. Analysis by Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre Responsibility for data collection: Natural England. Habitat quality Key data: Selected priority habitat extent and condition. Current position for chalk downland: 5,608ha within the National Park with 45 per cent designated as SSSI, and 56 per cent of these assessed as being in favourable condition. Current position for lowland heathland: 1,544ha of lowland heathland within the National Park with 55 per cent designated as SSSI, and 19 per cent of these assessed as being in favourable condition. Current position for ancient woodland: 17,351ha within the National Park. The condition is not well known, apart from where it forms part of an SSSI, which is only 8 per cent of ancient woodland within the National Park. 70 per cent of the ancient woodland within SSSIs in the National Park is assessed as being in favourable condition. Data source: Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre, Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre, Natural England (2012) England SSSI Unit Condition Assessments, Natural England. Analysis by Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre Responsibility for data collection: Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre and Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre, Natural England. Ecological status of rivers and lakes Key data: Water Framework Directive monitoring. Current position for the SDNP: 15 per cent of rivers are classified as ‘good or high ecological status’. 9.7 per cent of lakes are classified as ‘good or high ecological status’. Data source: Environment Agency (2012) Water Framework Directive Data, Environment Agency. Responsibility for data collection: Environment Agency. Habitat specialist butterflies Key data: Defra national biodiversity indicator.16 Pearl-bordered fritillary (woodland specialist): Current position: The national population declined by 60 per cent between 1970 and 1998, and declined by a further third by 2004. Although the National Park retains some colonies (most notably Rewell Wood in West Sussex), the national trend has been mirrored here with reduced numbers of sites and generally dwindling colony sizes. Adonis blue (chalk downland specialist): Current position: While subject to a long-term decline in numbers in Britain, the Adonis blue has shown some signs of recovery since the early 1980s. The past decade has seen the small and fragmented populations of the National Park gradually increase in size, particularly in the east. Silver-studded blue (heathland specialist): Current position: Silver-studded blue populations have declined both nationally and in the National Park over the last century with accelerated rates of decline over the past few decades (breeding records have declined by nearly half over the past 30 years). Populations in the National Park are mostly small and isolated. Populations on Iping and Stedham commons have recovered and stabilised after near extinction on these sites. Data source: Butterfly Conservation, Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre and Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre Responsibility for data collection: Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre and Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre. Wetland specialist species Key data: Water vole population. Current position: The water vole is Britain’s fastest declining mammal with the national population declining by 90–95 per cent over the past few decades. This decline has been mirrored in the National Park. However, the last few years there have been signs of a promising population recovery in some parts of the National Park. Data source: Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre and Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre Responsibility for data collection: Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre and Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre.

|

Climate Change Fact File

Climate Change Fact File |

Footnotes

Click on the footnote number to take you back to your place in the document.

1 South Downs National Park Authority (2011) Special Qualities of the South Downs National Park, South Downs National Park Authority

2 Defra (2011) Biodiversity Indicators in Your Pocket, Defra (National biodiversity indicators)

3 Hampshire and Sussex Biodiversity Record Centres

4 Defra (2011) Natural Environment White Paper for England, Defra

5 Environment Agency (2000) EU Water Framework Directive, Environment Agency

6 Hampshire and Sussex Biodiversity Record Centres (2010) (Target Area Identification)

7 In the UK, all National Nature Reserves, Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas are also designated SSSIs

8 Ibid

9 Information derived from Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre and Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre datasets in 2010

10 Victoria Hume and Matthew Grose (2010) West Sussex Ancient Woodland Survey Report:Weald and Downs Ancient Woodland Survey 2007–2010, Sussex Biodiversity Centre

11 Natural England (1995) South Downs Natural Area Profile, Natural England

12 Defra/Forestry Commission England (2005) Keepers of Time: A Statement of Policy for England’s Ancient and Native Woodland, Defra/Forestry Commission

13 Environment Agency (2006) The Test and Itchen Catchment Abstraction Management Strategy, Environment Agency

14 Nigel Holmes (2010) Sussex Chalk Streams Report,

15 Environment Agency (2009) South East River Basin Management Plan, Environment Agency

%20Ne_fmt.png)

%20Gemma%20Ha_fmt.png)