Chapter 2

Diverse, inspirational landscapes and breathtaking views

The geology of the South Downs underpins so much of what makes up the special qualities of the area: its diverse landscapes, land use, buildings and culture. The rock types of the National Park are predominately chalk and the alternating greensands and clays that form the Western Weald. Over time a diversity of landscapes has been created in a relatively small area which is a key feature of the National Park. These vary from the wooded and heathland ridges on the greensand in the Western Weald to wide open downland on the chalk that spans the length of the National Park, both intersected by river valleys. Within these diverse landscapes are hidden villages, thriving market towns, farms both large and small, and historic estates, connected by a network of paths and lanes, many of which are ancient.

There are stunning, panoramic views to the sea and across the weald as you travel the hundred mile length of the South Downs Way from Winchester to Eastbourne, culminating in the impressive chalk cliffs at Seven Sisters. From near and far, the South Downs is an area of inspirational beauty that can lift the soul.1

The landscape of the South Downs National Park

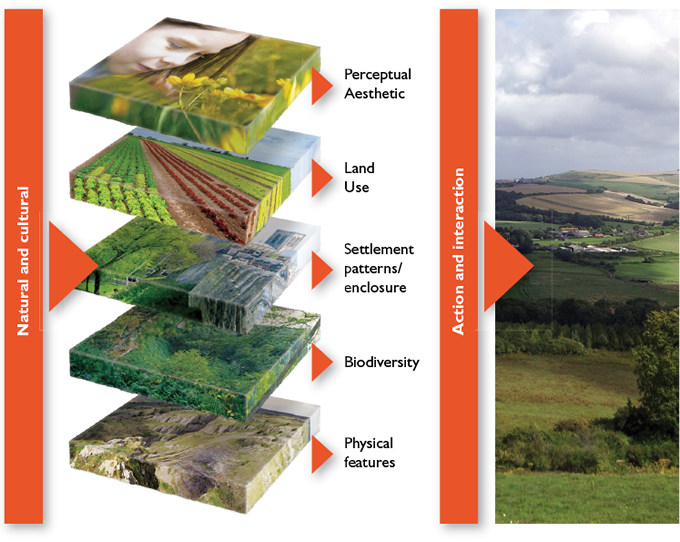

Landscape is more than scenery or a backdrop to our lives – it links culture with nature, and the past with the present. The landscapes of the National Park have been formed by the interaction of both natural factors such as geology, landform, soils and biodiversity; and cultural factors such as farming, land use, settlement patterns and other human activities. This interplay of natural and cultural influences has resulted in the National Park’s distinctive and diverse landscapes.

The resulting landscape ‘character’, and the ability to read the record of past activity in the landscape of the present,2 greatly influences the value we place on landscapes. Landscape is also important in terms of the benefits and services it provides us with, such as food, wildlife and clean water. It also helps to shape both our sense of place and of community.

To the east the open downland culminates in the spectacular chalk cliffs at Seven Sisters and Beachy Head, giving stunning panoramic views to the sea and northwards across the weald. The chalk ridge, which is further sculpted by steep coombes and dry valleys and is cut through north to south by four major river valleys, extends westwards with steep north facing escarpments3 and gentler south facing dip slopes4. This more westerly downland is more expansive, wooded and enclosed but no less impressive. It merges into the Hampshire Downs with their own dramatic east-facing escarpment to the west of Petersfield.

Figure 2.1 How landscape ‘character’ is formed

Photo © Amanda Davey

A series of equally impressive, greensand ridges lie to the north of the South Downs escarpment, and to the east of the Hampshire Downs escarpment (See Map 2.2). This area and its hinterland contain the intimate network of lanes, hedges and wooded heaths of the Western Weald.

Heathland at Iping Common © SDNPA

Devil’s Dyke © Helen Pearce

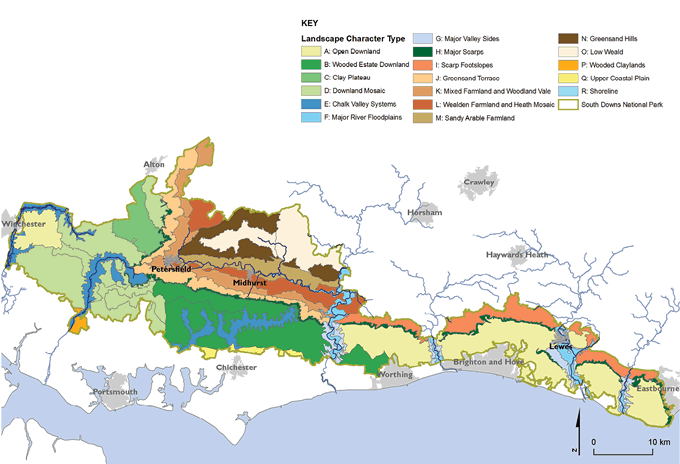

A Landscape Character Assessment (LCA) is a way of classifying, mapping and describing the characteristics of a landscape. It provides a framework within which important elements of the landscape can be maintained, change can be managed and positive environmental benefits secured.

The National Park has a rich and complex landscape character, with significant local variation and contrast. The South Downs Integrated Landscape Character Assessment (2005) provides the most current assessment within the area, highlighting this diversity by recognising 18 landscape types and a further 49 place-specific ‘character areas’ (see Map 2.1).

The assessment was updated in 2011, primarily to include the additional areas brought within the final boundary of the National Park. These include significant areas of land around Alice Holt, Tide Mills and Rowlands Castle.

For more information on landscape types and character areas that are found within the National Park. |

Map 2.1

The landscape character ‘types’ that make up the South Downs National Park

Maps prepared by: GeoSpec, University of Brighton; February 2012.

Source: South Downs National Park Landscape Character Assessment, South Downs National Park Authority, 2011

Ordnance Survey Crown Copyright © Licence No. 100050083.

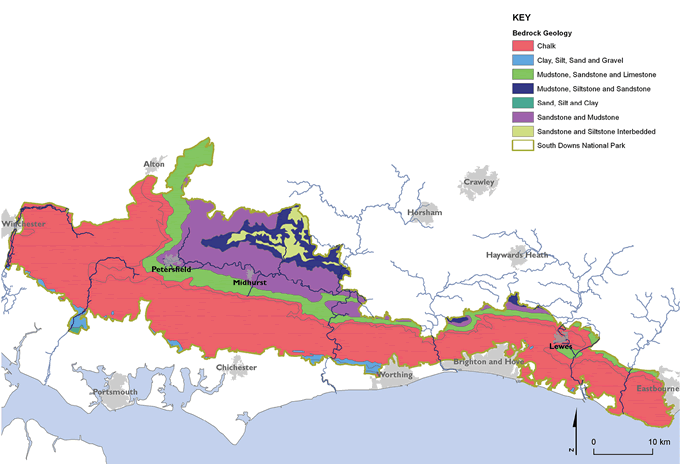

Geology and landform

The chalk of the South Downs was formed by marine deposits laid down when this part of Britain was covered by warm, tropical seas between 65 and 100 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period. The layers of chalk also contain bands of flint nodules, a common feature of the walls and buildings within the downland villages.

For how flint is formed. |

Chalk cliffs and beach © Countryside Agency

The chalk sits on top of earlier marine deposits of greensands and gault clay, and terrestrial deposits of the wealden sandstones and clays, all laid down during the 45 million years before the chalk. These layers (or ‘strata’) were pushed up and folded into a huge dome by the same powerful geological processes that formed the Alps.

|

Case Study Professor Rory Mortimore

Professor Rory Mortimore is a geologist and expert on the chalk of the South Downs who lives in Lewes and works in the South Downs National Park. He has dedicated 40 years of his life to the study of South Downs chalk, including its geology. “My particular interest is unlocking the evidence for and the causes of the exceptionally high former sea-levels (200–300 metres above present day) that led to the chalk-forming seas which covered the British Isles, and the causes and timings of the great earth movements that uplifted the weald and the downs into their present configuration. I’m also working with water companies and the Environment Agency to investigate how the chalk aquifer’s geology controls the mechanisms that store and release groundwater. This will help us to understand how to better manage water resources in the South Downs. Every day, as I walk my dogs on the South Downs, new ideas about the origins of this mutton-covered landscape constantly come to my mind. There is nothing more rewarding than taking parties of enthusiasts to the cliffs and quarries of the South Downs, exploring the geology and discussing these ideas.” |

Over millions of years this dome was eroded by weathering, especially during the ice ages. The South and North Downs are all that remains of this dome of chalk.

Erosion and weathering of the chalk during the ice ages produced a wide variety of contrasting landforms including the characteristic ‘rolling’ downland, the steep escarpments, deep coombes and dry valley systems.

The present day coastline was created about 10,000 years ago when melting ice caused sea levels to rise. The sea then eroded the base of the soft chalk cliffs, forming an overhang, which eventually collapsed. This caused the coast to retreat, resulting in the iconic chalk cliffs that we see today.

In the east the ridge itself is broken into distinct chalk blocks by the river valleys of the Arun, Adur, Ouse and Cuckmere. Further west, in the Hampshire Downs, the chalk ridge merges into a gentler, undulating, chalk plateau.

Although the chalk ridge visually dominates, other landforms also contribute to the National Park’s distinctive character. The greensands in the Western Weald were also created from sea-deposited sands and clays that once were covered entirely by the chalk. Over geological time these were weathered away to leave layers of lower and upper greensand and clays, and they share a similar scarp and dip slope topography to the chalk. The chalk and the lower greensand are separated by a ‘terrace’ of upper greensand and a band of low-lying gault clay.

In the coastal plain to the south of the chalk ridge the chalk is covered by younger rocks formed during the Tertiary period. Only a small part of this coastal plain is within the National Park.

For further information on the drift geology of the National Park. |

Designated Geological Sites

There are ten geological Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) within the National Park:

Brighton to Newhaven Cliffs;

Seaford to Beachy Head;

Beeding to Newtimber Hill;

Butser Hill;

Eartham Pit;

Horton Clay Pit;

Southerham Worles Pit;

Southerham Grey Pit;

Southerham Work Pit; and

Asham Quarry.

Details of individual Sites of Special Scientific Interest can be found at:

| www.sssi.naturalengland.org.uk/Special/sssi/search.cfm |

There are a further 50 sites within the National Park that are important in terms of their geology. These are usually notified as Local Geological Sites (LGS).

For a Map of RIGS |

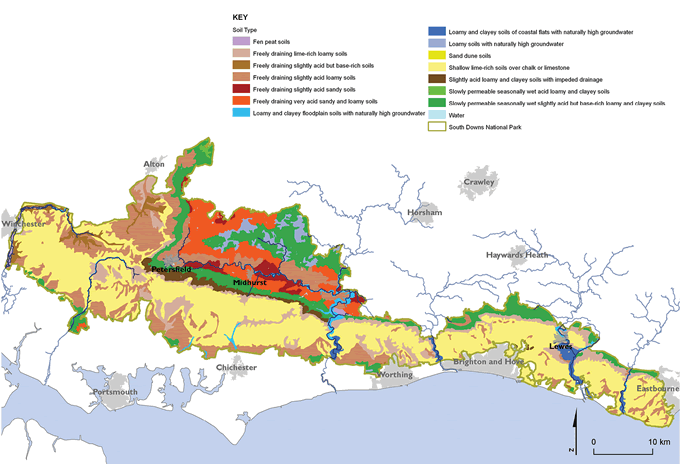

Soils

The soils derived from the chalk are mostly thin, well drained and poor in both minerals and nutrients. They only support slow rates of plant growth, which is why specialist chalk grassland species are a feature in surviving fragments of unimproved land. Areas of deeper soils, with better fertility, are found on the dip slope and in valley bottoms. In a few places, such as at Lullington Heath, wind-blown soils called ‘loess’ have been deposited on top of the chalk. This is thought to have been laid down during the last ice age. It often supports rare habitat types such as chalk ‘heath’, which are nationally important.

The sandy soils of the wealden greensand are acidic and also nutrient-poor. These are most often associated with the wooded heaths and commons such as those at Stedham, Graffham and Duncton. Between the chalk and the greensand lies a band of highly fertile soil over gault clay.

Water and hydrology

The Water Fact File which follows Chapter 3 sets out the important facts about water and the National Park, including the chalk aquifer that stores water under the South Downs.

Map 2.2

The solid (bedrock) geology of the South Downs National Park

Maps prepared by: GeoSpec, University of Brighton; February 2012.

Source: British Geological Survey, 2008

Ordnance Survey Crown Copyright © Licence No. 100050083.

Map 2.3

Main soil types found within the South Downs National Park

Maps prepared by: GeoSpec, University of Brighton; February 2012.

Source: National Soil Resources Institute, Cranfield University, 2001

Ordnance Survey Crown Copyright © Licence No. 100050083.

Marine and coastal processes

There is 20.5km of dramatic and continuously changing coastline in the National Park. The effects of wave erosion and the instability of the chalk cliffs are starkly evident along the dramatic sea cliffs of Beachy Head and the Seven Sisters. There were significant major cliff falls as recently as April 2001. Current rates of erosion on this section of coastline range between 10cm and 50cm per year.

These natural processes of erosion can be modified with the construction of seawalls and coastal defences, which often affect or disrupt erosion rates and the deposit of sediments further along the coast. Some coastal beaches are starved of sediment and various engineering techniques have been used to address this problem. In some cases these engineering works can also affect the scenic quality and unspoilt nature of the landscape.

Estuaries, such as the Cuckmere, are a crucial component of drainage within coastal areas, taking surface water downstream and into the sea. Where drainage of either the estuary itself or its tributaries is blocked this can create localised flooding. Estuaries are hugely important in recycling nutrients and supporting the food chain within the marine environment.

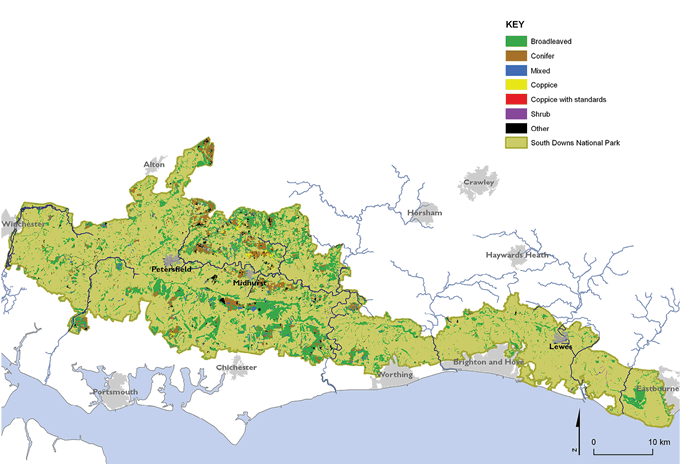

Trees and woodland in the landscape

Woodland forms a very significant feature of the landscapes of the National Park, particularly in the central and western downs and on the wealden greensand.

In this chapter woodland is treated as a component of landscape. More detail on woodland ecology, cover, distribution and composition can be found in later chapters.

Ashford Hangers © Charles Cuthbert

See Map 2.4 for the spatial distribution of woodland types within the National Park.

For more information on the extent of woodland within the National Park. |

The National Park also has a significant number of ancient and veteran trees, such as the Queen Elizabeth oak on the Cowdray Estate. These are often iconic landscape trees, with significant historic, cultural and biodiversity value.

Other trees of significant landscape value include the surviving populations of English elms, rare populations of black poplar in the Ouse Valley and around Lewes, and the mature sweet chestnut that feature within estate landscapes such as at Stansted. They require special consideration and management in terms of their succession.

The cultural landscapes of the South Downs

The landscapes of the National Park have changed through time, telling a vivid story of how, for thousands of years, the natural environment and human settlement have influenced each other.

_fmt.png)

Long Man of Wilmington © NE/Peter Greenhalf

Map 2.4

Main woodland types within the National Park area

Maps prepared by: GeoSpec, University of Brighton; June 2012.

Source: National Forest Inventory, Forestry Commission, 2011

Ordnance Survey Crown Copyright © Licence No. 100050083.

Historic landscape change

|

Case Study Dr Nicola Banister Dr Nicola Banister is an independent Landscape Archaeologist with over 20 years of experience of surveying and recording woodland archaeology and historic landscapes in the south and south east of England. As well as undertaking a number of detailed historic landscape surveys on the South Downs she has also completed the Sussex Historic Landscape Characterisation Map – which benchmarks the current state of the county’s landscape and acts as a tool for guiding future management that recognises the history and processes which have shaped it. “You can see the history of the South Downs written on the landscape today in places such as the top of the chalk escarpments where Neolithic and Bronze Age woodland was cleared for livestock grazing and early agriculture. Evidence of human intervention over thousands of years survives in strip lynchets, field systems, round barrows, territorial boundaries such as cross dykes and hillforts across the National Park. This human interaction with the landscape continues today with many historic features such as ancient routeways, field boundaries, and settlement sites still in use. Understanding the processes which developed this historic character will be important for informing future decisions about how to manage the landscape to retain this historic character.” |

The characteristic open and treeless aspect of the eastern half of the South Downs is the result of Neolithic and Bronze Age woodland clearance for livestock grazing and early agriculture. During the Bronze Age there was a return to more nomadic farming. By the Iron Age, hillforts such as at Cissbury were centres of economic activity. During the periods of the Roman occupation there is evidence that the area was farmed very intensively. There are remains of large Roman farmsteads and estates across the National Park, such as the nationally important site at Bignor.

Up until the late 18th century, the agricultural economy generally moved between extensive livestock grazing and arable crops, in response to market conditions – such as when wool was a high value product in the 16th/17th centuries. Arable production has historically been on the better soils on the valley bottoms and dip slopes, with a move to higher ground when demand or price was greater.

In the central downlands, there was less woodland clearance, and a greater area of ancient woodland remains. Big estates continued to be a feature during the Saxon and Medieval period, with the Church being the principal landowner. With the dissolution of the monasteries in the early 16th century the land was sold by Henry VIII and moved into secular hands. This led to the development of the large country houses and estates that remain a notable feature of the central downlands. The prominent parkland landscapes, influenced by the English Landscape Movement, are largely a development of the Georgian period.

To the west, large woodland areas remain, with hedgerow and field patterns that survive from Medieval times. These are surviving remnants of the ‘assart’5 landscapes, which demonstrate a historic link between the weald and the downlands. Field patterns and enclosure across the wider South Downs are generally more typical of the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Western Weald has also been settled since prehistoric times, with Neolithic remains being found around Woolmer Forest. Traditionally a wooded and grazed landscape, it has significant surviving areas of common land and wooded heath. Poor soils saved these areas from early woodland clearances and fragmented areas of ancient woodland also survive here.

Fernhurst Sluice, near Fernhurst © Helen Pearce

The early iron industry, using local timber and ironstone, was also a significant feature of the Western Weald, with the remains of old quarries and hammer ponds still to be seen. More recently, the area of heathland has declined due to lack of management, conversion to arable land and development.

The rivers of the National Park have played an important role:

as transport conduits allowing trade to and from the South Downs; and

to generate energy, with water and ‘tide’ mills being used to mill grain, for example, at Bishopstone in East Sussex which operated until 1883.

Over time, siltation of the rivers affected their natural course, with historic inland ports such as Steyning and Arundel becoming land locked.

Modern development is particularly concentrated at the eastern end of the National Park with coastal towns such as Brighton and Worthing expanding along the coast and up onto the South Downs. Much of this growth occurred during the latter part of the 19th and the 20th century.

Post war development, mainly after World War I, expanded out from the settlements along the coast. This was often unplanned and uncontrolled, and spread along the whole coastal plain adjoining the National Park. A few stretches of coastal chalk cliffs remained undeveloped such as the section between Seaford Head and Beachy Head. Timely intervention and lobbying during the 1920s and 1930s began the journey to conserve the beauty of this iconic coastline.

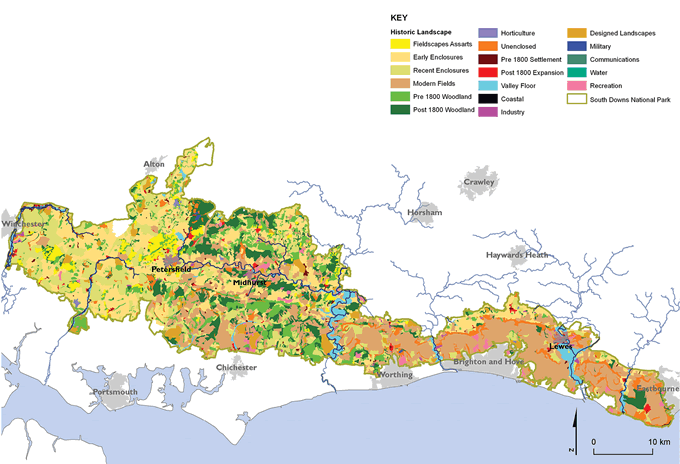

A way to understand the historic character of the landscape, and how past activities have shaped it, is through the Historic Landscape Character Assessments. These have been published for East Sussex, West Sussex and Hampshire, and provide greater detail of historic settlement and field patterns and evidence of other land use change over time. The integrated Landscape Character Assessment also includes a classification of historic landscape types (see Map 2.5).

| www.southdowns.gov.uk/planning/integrated-landscape-character-assessment |

Landscape change: Recent trends and changes

Significant areas of the unimproved downland were ploughed as part of the drive for self-sufficiency during World War II. The subsequent 50 years have seen further changes. Agricultural intensification has continued, with increases in arable and improved grassland crops. There has been a decline in species-rich chalk grassland, which is now mainly confined to the steep escarpments and valley slopes:

Drainage and agricultural improvement of river valley floodplains, with the lowering of water tables, has altered their traditional landscape character. There has been a loss of wet pastures and historic boundary features such as hedgerows. This has led to a more formal pattern of arable fields along the river valleys, such as in the Arun, Ouse and Cuckmere.

The decline of traditional practices, such as extensive sheep grazing, has led to scrub encroachment on the fragments of chalk grassland that remain. However, an increase in new grassland area, and uptake of agri-environment schemes, suggests that some elements of landscape character have been enhanced. There has been some increase in hedgerow planting, and restoration of historic farm buildings and features due to these schemes.

Agricultural practices and trends also influence landscape character such as extensive planting of crops like oilseed or flax, resulting in distinctive swathes of yellow or blue. The increased planting of vines, or growing of crops under fleece to extend the growing season, also changes visual character.

Woodland in the National Park, despite pretty constant levels, has been affected by a lack of traditional management, with many of the surviving hazel and chestnut coppices falling into dereliction and consequently the quality of the woodland for biodiversity is declining.

There has also been a loss and decline in the landscape quality of beech hangers and woodlands in the western chalk escarpment due to lack of management and storm damage. However, this has had benefits in terms of biodiversity, opening up glades for other plant species to move in under previously dense canopy.

New woodland planting has assisted with natural regeneration and in linking fragmented semi-natural ancient woodland sites. However, new woodland planting has also occurred in some inappropriate locations such as the open downs to the east.

Between 2005–2011, the area covered by Woodland Grant Management schemes increased to 14,720ha which represents 38 per cent of the total woodland cover. This suggests that a greater area of woodland is being positively managed.6

|

Box 2.1 Pressures on the landscape To date, most of the key aspects of the landscape character have been maintained. However, gradual and incremental changes can add up and, over time, lead to significant loss of local distinctiveness and ‘sense of place’. The open downland has been vulnerable to urban edge pressures extending from the heavily built-up areas and coastal fringe adjoining the National Park. Communication masts and pylons on exposed skylines are prominent within the landscape, and are often significant detractors. Disused chalk quarries are also prominent features, and have often been utilised as major landfill sites. All these have an impact on landscape character and quality. Pressures for road improvements, often with major cuttings and/or tunnels, have been an issue in the eastern downs and the Hampshire Downs to the west. This has led to reduced perceptions of tranquillity in open downland landscapes, especially adjacent to urban conurbations. There has been some deterioration of historic farm buildings as they have fallen out of use, but there is also a continuing trend in conversion to residential use. In the settlements and villages, new development has not always reflected local character in terms of traditional design and materials. This has led to increased urbanisation and some loss of local distinctiveness. Loss of historic features and local vernacular can also have an effect, such as the loss of traditional wooden signage, and replacement with standardised metal signage. Infrastructure development (for utilities etc), often does not require planning permission and can have significant impacts on landscape character. However, there have been some improvements, such as efforts to lessen the impact of power lines, like the successful undergrounding scheme at Birling Gap. |

Map 2.5

The historic landscape character ‘types’ within the South Downs National Park

Maps prepared by: GeoSpec, University of Brighton; February 2012.

Source: South Downs National Park Landscape Character Assessment, South Downs National Park Authority, 2011.

Ordnance Survey Crown Copyright © Licence No. 100050083.

|

Key data: Diverse, inspirational landscapes and breathtaking views Landscape character The National Park Authority, with its partners, will assess the landscape character of the National Park, and monitor broad changes in landscape character: Key data: Integrated Landscape Character Assessment (LCA); Landcover Mapping Data and Aerial Photography. Current position: Recently updated to cover the National Park area, landscape classification still fit for purpose, further updating should be carried out within the life of the Management Plan. Key data: Historic Landscape Characterisation (HLC). Current position: Recently updated, further updating required to monitor changes in the historic landscape character of the National Park. Data sources: Land Use Consultants (2011) South Downs National Park Integrated Landscape Character Assessment, Land Use Consultants; Archaeology South-East (2011) Revised Landscape Character Assessment – Additional Historic Landscape Characterisation, Archaeology South-East; Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (2011) Land Cover Map 2007, Centre for Ecology & Hydrology Responsibility for data collection: South Downs National Park Authority, county and district councils and English Heritage. Geological SSSIs and Local Geological Sites (LGS) The National Park Authority, with its partners, will monitor the condition of designated geological sites within the National Park to ensure they are being appropriately managed, and the features for which they were designated are being maintained: Key data: Monitoring data for Geological SSSIs and LGS. Current Position: Geological sites within East and West Sussex have recently been surveyed (2010/11), and their condition is being maintained. There is less data for Hampshire, with only one local site having been designated. This may be a case of under-reporting due to not having an active local geodiversity group in that area – we are working with partners to help set up such a group. Data source: Sussex Biodiversity Records Centre and Hampshire Biodiversity Records Centre Responsibility for data collection: County environmental records centres and local geological groups. Woodland as a landscape feature The National Park Authority, with its partners, will monitor the condition of ancient and semi-natural woodland features within the National Park: Key data: National Inventory for woodland and trees; uptake of woodland grant schemes for improved management. Current Position: Between 2005–2011, the area covered by Woodland Grant Management schemes increased to 14,720ha, 38 per cent of the total woodland cover. This increased uptake of these schemes suggests that a greater area of woodland is being positively managed. However, much of the woodland within the National Park is not being actively managed. Data source: Forestry Commission (2011) National Forest Inventory, Forestry Commission; Natural England (2012) Protected Landscapes Data, Natural England Responsibility for data collection: Forestry Commission and Natural England.

|

Footnotes

Click on the footnote number to take you back to your place in the document.

1 South Downs National Park Authority (2011) Special Qualities of the South Downs National Park, South Downs National Park Authority

2 Time-depth: The visible evidence in the landscape for change and continuity over periods of time

3 The surface of the steep slope is called a scarp face or escarpment

4 Scarp and dip slopes are geological features found on large ridges such as the South Downs where one side is steep and irregular (scarp slope) and the other side (dip slope) is generally flatter and tilts at a continuous angle

5 Assarts were generally small, irregular fields cut out from woodland or heathland areas, some of these early enclosure patterns have survived from Medieval times

6 Natural England (unpublished) Draft National Character Area Profiles, Natural England