Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

Timeless quality, constant change

The South Downs National Park is a special place, with visitors from near and far amazed to find so much beauty and diversity just a stone’s throw from London. It represents outstanding examples of lowland landscapes1 in the UK. From the dramatic chalk cliffs at Beachy Head, the chalk escarpment runs 114km westward, culminating in the wide open sweep of the arable Hampshire Downs. To the north of the West Sussex Downs, before the edge of the chalk turns northwards at Petersfield, lies the intimate patchwork of woodland and heathland of the Western Weald rising to the isolated splendour of Blackdown.

This is not an untouched wilderness, however, but a living, working place that has evolved over several thousand years of complex interplay between people and place, an interplay which continues to this day.

The very accessibility of this part of England, and the ease with which the chalk hills, in particular, could originally be cleared and settled, means that almost every stage of the human story of Britain, its history and culture, is woven into the very fabric of the land.

As people have shaped these landscapes, so too have the landscapes shaped the communities. The geology, topography2 and natural resources of the National Park have influenced the patterns of agriculture, settlement, industry and culture, and the places we now see as special are the product of this interaction.

In Britain, it is easy to take for granted the continued existence of the sort of living, working ‘cultural landscapes’ which exist in the National Park, yet they are important on a global scale. Our familiar landscapes hide within them environmental and cultural treasures no less important than those of the world’s great wilderness national parks or the rich urban environments of international cities, and they exist in marked contrast to the large-scale intensive agricultural monocultures3 which now dominate many lowland zones. This distinctiveness is recognised by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).4

It is for all these reasons that the Order for Designation for the area of the South Downs and Western Weald to become Britain’s newest National Park was made in 2002. With an area of 1,653km2 (618 miles2), it includes heritage coast, farmland and woodland, National Nature Reserves, historic monuments, visitor attractions, listed buildings and Conservation Areas. There are thousands of archaeological features, as well as parks and gardens, historic houses, market towns and villages. It is also a landscape that has attracted and inspired artists, writers and musicians from Eric Ravilious to Jane Austen, Rudyard Kipling, Elgar, John Ireland and Gilbert White, to name but a few. This rich cultural heritage lives on in the many works of art and artefacts held in country houses and museums throughout the area, and still grows as creative individuals continue to be inspired by the National Park’s special qualities.

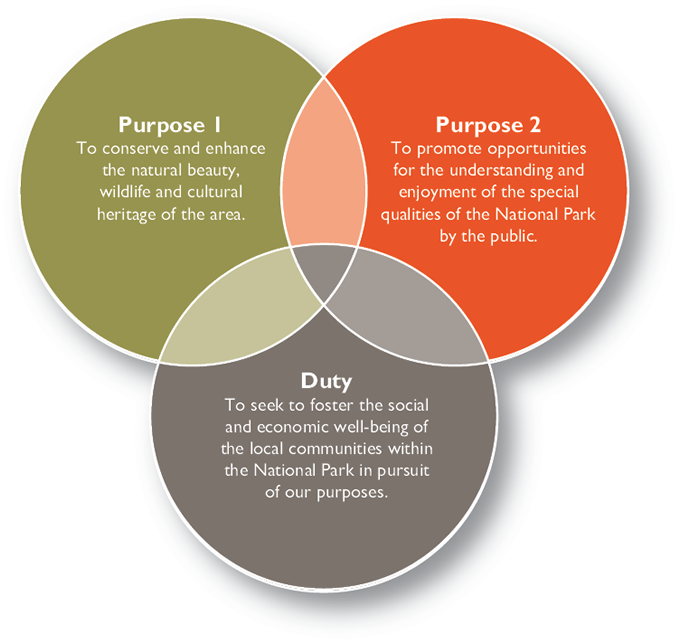

Over 110,000 people live in the market towns, villages and countryside of the National Park, and 1.97 million more live right on its doorstep. This sets the South Downs National Park apart from many of Britain’s 13 other national parks the majority of which, though they all include living, working and populated landscapes, have far fewer people in and immediately around them. Its future, like its past, is interdependent with the areas that adjoin it – both its landscape and its residents’ best interests are served by close working partnerships across its borders. The creation of the National Park provides an opportunity to ensure that its future stewardship brings benefits to people within and around it, as well as those much further afield who love and cherish it. With those benefits come responsibilities. This interdependence is recognised in the Purposes for which national parks are established, and the Duty which is placed on the National Park Authority itself:

Figure 1.1 Purposes and duty of the National Park

The designation of the National Park is not about creating an island within which some mythical rural idyll can be recreated. Change has been a constant factor in shaping its special qualities: flint gave way to bronze, then iron; the economics of agriculture saw the balance between sheep and corn on the South Downs fluctuate many times; populations have ebbed and flowed; the creation of the large estates led to new, designed, landscapes. It will continue to be subject to substantial external influences over the next few years including:

the profound and long-term effects of climate change and our responses

to it;

changes in the rural and agricultural economy; and

migration and an ageing population.

It is the job of the National Park Management Plan, built on the foundations of this report, to find an appropriate response to these and other influences, to build a shared vision of the future and to inspire and engage the people, communities and organisations who live in, work in or visit the area. Our challenge will be to ensure that however different the future looks the special qualities of the National Park endure.

A snapshot based on existing data

This is the first State of the South Downs National Park report, and the National Park Authority has worked closely with many organisations and individuals to create it. Produced just 18 months after we became operational, this publication draws largely on existing data from local authorities, statutory agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). All of these bodies have information on the area of the National Park, but the degree to which this can be mapped to the National Park boundary varies widely. The National Census data, for example, is quite old as up-to-date information, cut to the boundary, will not be available until after publication. The report must be read with these caveats in mind.

Despite all the limitations imposed by existing data, a picture does begin to emerge, in words and images, of the National Park as it is today, a baseline against which future changes can be measured. We have striven to ensure that the style and tone of the report, and the choice of data referred to within it, is as value-neutral as possible: the place for making judgements about how to tackle the complex issues that emerge from it is the upcoming Management Plan.

For ease of use, each of the main chapters of the report highlights key facts and key data. The latter are datasets which we and our partners have made a commitment to monitor and update on a regular basis. For example, in Chapter 7: Well-conserved historic features and a rich cultural heritage, we will work with English Heritage to monitor the number of ‘heritage at risk’ sites in the National Park.

We are also creating an online version of this report to which we will regularly add new and updated data when it becomes available.

Where you see the icon below in this report you can go to the online version to find additional information and links to the key information sources or evidence used (where available). We would like the online version to be a reference point for both members of the public and specialists with a keen interest in the detail behind this report. In a number of places, you will see a help icon.

![]()

This highlights areas where insufficient information currently exists on important topics and where we are inviting proposals for data gathering.

![]()

This indicates where you can find additional information on our website or from external sources.

![]()

Use of statistics

The use of averages in many of the datasets in this report does create particular challenges in a National Park as large and varied as this one. The presence of towns like Petersfield and Lewes, and the variations which occur in so many attributes (such as rainfall and house prices) from east to west, mean that all the mean averages, though in themselves are accurate, need to be treated with caution.

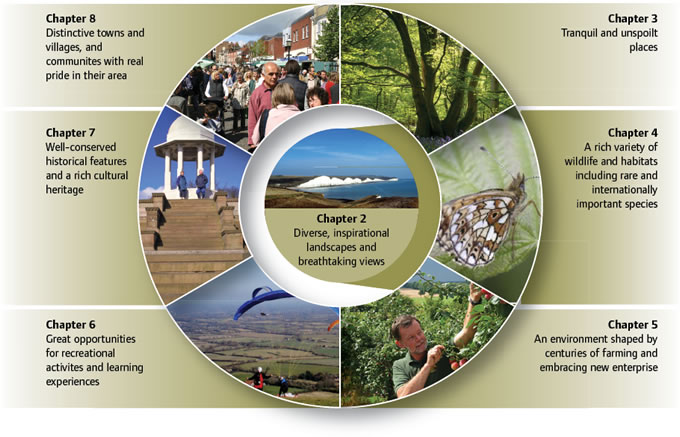

Figure 1.2 The seven special qualities of the South Downs National Park

Special qualities

A crucial starting point for managing change in the future is to capture the essence of what makes the National Park important now – its special qualities. Every national park has developed a list of the things that make it special, both as a baseline for measuring changes over time and to hold the National Park Authority and its partners to account for their contributions to its future.

In the case of the South Downs, we were particularly keen to ensure that the special qualities reflected the views of the people living in and around the National Park. To this end we asked residents and visitors, landowners and farmers, businesses, school pupils, parish councils and many others to put forward their ideas. The seven special qualities arose directly from this work, and the chapters that follow are structured around these special qualities.

The special qualities do not sit in isolation. Rather, they are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Landscape is the key to all of the other special qualities and is therefore shown at the centre of Figure 1.2.

The published special qualities can be found on our website:

| www.southdowns.gov.uk/about-us/special-qualities |

Creating the whole picture

Although the seven special qualities capture much of the essence of the National Park and what creates its ‘sense of place’, they cannot paint the whole picture. They are perhaps better thought of as a way of measuring our ‘stocks’, the assets which we have inherited and wish to pass on to future generations. The aim behind the National Park designation must be to conserve and enhance all seven together.

At the heart of this challenge lies the quality of the relationship between people and landscapes and places. Being a new national park gives us the opportunity to understand more about how to measure and value this relationship, and this in turn will help us to find ways of building a virtuous circle between the two – to promote activities and enterprises which benefit people and landscapes and places at the same time. This means we can start to measure how things interact as well as what they are.

In Figure 1.3 the grey arrow pointing to the right is about increasing the ways in which people can benefit the landscapes and places of the National Park – not just enjoying and understanding, but making a contribution through more sustainable farming, as responsible visitors, as greener businesses, social enterprises, volunteers and as active communities.

Figure 1.3 The relationship between people and landscapes and places

The orange arrow pointing to the left in Figure 1.3 is about ensuring that the way we manage our landscapes and places provides the maximum, sustainable, benefits to the people who live in, work in or visit them. This is nothing new: our forebears in the Middle Ages were part of an economy that managed the landscape to produce a range of local resources such as timber, grazing, water and minerals: a mixed economy in which the presence of a springline or the availability of fuel and building materials was as important as crop production.

This simple and enduring principle known as ecosystem or ‘natural’ services would have been widely understood in previous centuries. Although the balance changed over time, the rural economy remained quite diverse in its use and management of natural resources until very recently. But rapid changes in technology and the availability of abundant, cheap, fossil fuel energy have made it profitable for the first time to grow crops intensively. This, for example, contributes to diffuse pollution of drinking water supplies which then have to be cleaned up at a cost to the public.

It is worth noting that as early as the nineteenth century enlightened and forward looking corporations in Brighton, Worthing and Eastbourne started to purchase large areas of downland in order to secure the water supply on which their own residents relied.

Ecosystem services and benefits

Ecosystem services or ‘benefits from nature’ can be defined simply as the services provided by the natural environment that benefit people. There are four broad categories of services:5

|

|

Regulating services: such as water purification, air quality, flood protection and climate regulation |

|

|

Supporting services: functions that underpin all of the above, such as soil formation and nutrient cycling |

|

|

Cultural services: ‘non-material’ benefits such as physical well-being, education and inspiration |

|

|

Provisioning services: products such as food, water and raw materials |

The science, economics and national policy work around ecosystem services will provide a very important set of tools to help promote a more diverse, resilient and sustainable local economy.

Reviewing and updating the report

This first State of the South Downs National Park report establishes a baseline and explains the ‘key data’ we intend to measure. Each of the key data may be measured at different times, some each year and some less frequently. In some cases you will see from the report that we are responsible for collecting the data, in others it will be one of our partner organisations such as Natural England, or a Government Department such as the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Some new work – for example, about the character of the landscapes – has already been completed and is included in this report. Work to fill other evidence gaps, such as the visitor and residents survey, has been commissioned but is not yet completed. As we complete new evidence work, we will make it available on our website.

The key data in this report is shown at the end of the relevant chapters (2–8) and will also be made available on our website.

We intend to review the major changes in the State of the South Downs National Park report at the same time as we carry out the first review of the National Park Management Plan, which is likely to be in 2017.

Acknowledgements

We have used our own expert knowledge about landscapes, biodiversity, farming and the wider rural economy, recreation and learning, cultural heritage and communities to develop this report. At the same time, we have worked closely with, and benefitted enormously from, the expertise of many individuals and organisations.

Footnotes

Click on the footnote number to take you back to your place in the document.

1 In physical geography, a lowland is any broad expanse of land with a general low level

2 The surface shape and features of an area

3 The cultivation of a single crop on a farm or in a region or country

4 A protected area where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced a distinct character with significant ecological, biological, cultural and scenic value; and where safeguarding the integrity of this interaction is vital to protecting and sustaining the area and its associated nature conservation and other values; (1994) Management Guidelines for IUCN Category V Protected Landscapes/Seascapes